Democratic Republic of Congo, Involvement of MONUSCO

Case prepared by Ms. Anaïs Maroonian, Master student at the Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva, under the supervision of Professor Marco Sassòli and Ms. Gaetane Cornet, research assistant.

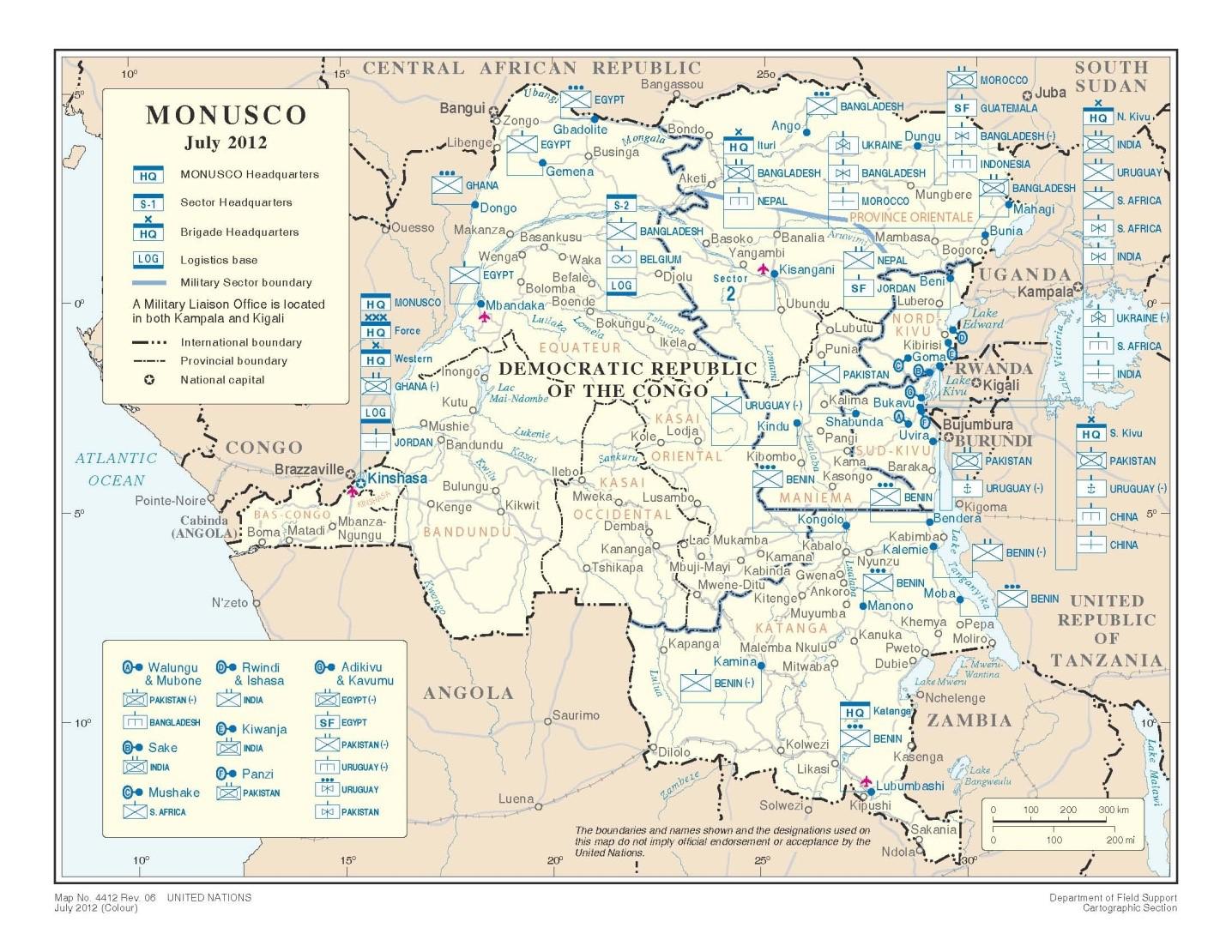

[Source : “MONUSCO, July 2012”, Map No. 441 Rev.06 UNITED NATIONS, available at: http://www.operationspaix.net]

A. Security Council Resolution 2053 (2012)

N.B. As per the disclaimer, neither the ICRC nor the authors can be identified with the opinions expressed in the Cases and Documents. Some cases even come to solutions that clearly violate IHL. They are nevertheless worthy of discussion, if only to raise a challenge to display more humanity in armed conflicts. Similarly, in some of the texts used in the case studies, the facts may not always be proven; nevertheless, they have been selected because they highlight interesting IHL issues and are thus published for didactic purposes.

[Source: UN Doc. S/RES/2053 (June 27, 2012). Available at: https://www.un.org]

SECURITY COUNCIL EXTENDS MANDATE OF UN MISSION IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

UNTIL 30 JUNE 2013, UNANIMOUSLY ADOPTING RESOLUTION 2053 (2012)

The Security Council this afternoon decided to extend until 30 June 2013 the mandate of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), reaffirming its priority of protection of civilians and urging Congolese authorities to reform their security sector and end armed insurgencies and abuse of human rights in the vast African country.

Through the unanimous adoption of resolution 2053 (2012), the Council renewed the mandate of MONUSCO unchanged, but reiterated that future reconfigurations of the Mission should be determined on the basis of the evolution of the situation on the ground, ending violence in the eastern provinces, security sector reform and consolidation of State authority throughout the national territory. [...]

“The Security Council, [...]

“Acknowledging that there have been positive developments relative to the consolidation of peace and stability across the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but stressing that serious challenges remain, particularly in the eastern provinces, including the continued presence of armed groups in the Kivus and Oriental Province, serious abuses and violations of human rights and acts of violence against civilians, limited progress in building professional and accountable national security and rule of law institutions, and illegal exploitation of natural resources,

“Expressing deep concern at the deteriorating security situation in the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including attacks by armed groups, attacks on peacekeepers and humanitarian personnel, which have restricted humanitarian access to conflict areas where vulnerable civilian populations reside, and the displacement of tens of thousands of civilians, and calling on all armed groups to cease hostilities, including all acts of violence committed against civilians, and urgently facilitate unhindered humanitarian access, [...]

“Remaining greatly concerned by the humanitarian situation and the persistent high levels of violence and human rights abuses and violations against civilians, condemning in particular the targeted attacks against civilians, widespread sexual and gender-based violence, recruitment and use of children by parties to the conflict, in particular the mutineers of ex-Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (ex-CNDP) and the 23 March Movement (M23), the displacement of significant numbers of civilians, extrajudicial executions and arbitrary arrests and their deleterious effect on the stabilization, reconstruction and development efforts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, reiterating the urgent need for the swift prosecution of all perpetrators of human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations, urging the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in cooperation with the United Nations, the International Criminal Court and other relevant actors, to implement the appropriate responses to address these challenges and to provide security, medical, legal, humanitarian and other assistance to victims, [...]

“Welcoming the efforts of MONUSCO and international partners in delivering training in human rights, child protection and protection from sexual and gender-based violence for Congolese security forces and underlining its importance,

“Condemning all attacks against United Nations peacekeepers and humanitarian personnel, regardless of their perpetrators and emphasizing that those responsible for such attacks must be brought to justice, [...]

“Determining that the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo continues to pose a threat to international peace and security in the region,

“Acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations: [...]

“1. Decides to extend until 30 June 2013 the mandate of MONUSCO as set out in the resolution 1925 paragraphs 2, 11 and 12 (a) to (p) and (r) to (t), reaffirms that the protection of civilians must be given priority in decisions about the use of available capacity and resources and encourages further the use of innovative measures implemented by MONUSCO in the protection of civilians; [...]

“11. […e]ncourages the Government to ensure that members of the National Army are adequately paid and in a timely fashion, operate in accordance with established command and control regulations, and are subject to such disciplinary or judicial action as may be appropriate when regulations and laws are violated and reiterates its concern at the promotion within the Congolese security forces of well-known individuals responsible for serious human rights violations and abuses; [...]

“13. Further stresses the importance of the Congolese Government actively seeking to hold accountable those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the country and of regional cooperation to this end, including through cooperation with the International Criminal Court, calls upon MONUSCO to support the Congolese authorities in this regard, and takes note of the recent positive steps taken by the Congolese authorities to apprehend Bosco Ntaganda; [...]

“18. Demands that all armed groups, in particular mutineers of ex-CNDP and M23, the FDLR, the LRA and the Allied Democratic Forces/National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (ADF/NALU), immediately cease all forms of violence and human rights abuses against the civilian population in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in particular against women and children, including rape and other forms of sexual abuse and child recruitment, and demobilize;

“19. Condemns recent mutiny led by Bosco Ntaganda and all outside support to all armed groups and demands that all forms of support to them cease immediately; [...]

“22. Underlines the urgent need for continued progress in addressing the threat of foreign and national armed groups, including through further progress in the DDRRR process, urges the international community and donors to support the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and MONUSCO in DDRRR activities, calls upon the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and neighbouring States to remain engaged in the process and urges the Government to make progress on the national programme for disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) of residual Congolese armed elements in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, with the support of MONUSCO;

“24. Encourages MONUSCO to enhance its interaction with the civilian population to raise awareness and understanding about its mandate and activities and to collect reliable information on violations and abuses of international humanitarian and human rights law perpetrated against civilians; [...]

“26. Demands that all parties cooperate fully with the operations of MONUSCO and allow, in accordance with relevant provisions of international law, the full, safe, immediate and unhindered access for United Nations and associated personnel in carrying out their mandate to all those in need and delivery of humanitarian assistance, in particular to internally displaced persons, throughout the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including in the LRA-affected areas, and requests the Secretary-General to report without delay any failure to comply with these demands; [...]

B. Security Council Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

[Source: UN Doc S/2013/96 ( February 15, 2013). Available at : http://www.un.org]

Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

I. Introduction

1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2053 (2012). In paragraph 28 of that resolution, the Council requested that I report, by 14 February 2013, on the progress on the ground in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including towards the objectives outlined in paragraph 4 of the resolution, and on recommended benchmarks for measuring the progress and the impact of the disarmament, demobilization, repatriation, resettlement and reintegration process on the strength of foreign armed groups. […] The present report covers developments that occurred since my report of 14 November 2012 (S/2012/838).

II. Major developments

2. The situation in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo remained fragile as elements from the former Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP), now known as the Mouvement du 23 mars (M23), further consolidated their control over a significant portion of North Kivu Province. On 20 November, after intense fighting involving the Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo (FARDC) and MONUSCO, M23 occupied Goma and withdrew from the city only on 2 December. In that context, attacks against civilians intensified and the humanitarian situation deteriorated significantly. Regional tensions were fuelled by reports of active external support continuing to be provided to M23. The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, with the support of other international and regional partners, was successful in facilitating the opening of a dialogue between the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and M23 in December. Despite a number of challenges and delays, those talks are continuing in Kampala. [...]

III. Implementation of the mandate of the mission

Protection of civilians

34. MONUSCO employed a series of flexible short-term measures to provide security in areas where civilians were under imminent threat. This included the use of quick reaction forces and standing and mobile patrols around hotspots in Goma during the hiatus between the withdrawal of M23 and the redeployment of the Congolese armed forces and the Congolese national police. MONUSCO assigned five quick reaction forces to protect the internally displaced persons camps and sites of Mugunga I and III, Bulengo and Lac Vert. The Mission maintained a round-the-clock presence outside the Mugunga III camp to conduct night patrols. In terms of additional measures to enhance the protection of internally displaced persons, the Mission extended the community alert networks to Mugunga I and III, Bulengo, Nzulo and Lac Vert. The number of officials responsible for internally displaced persons was increased in each camp and site.

35. MONUSCO deployed 82 community liaison assistants in Orientale Province and North Kivu between November 2012 and January 2013. During the reporting period, local communities and humanitarian actors alerted assistants about attacks or threats on 38 occasions, triggering a response from national security forces or MONUSCO. Assistants also worked on the extension of the existing community network in the Kivus and Orientale Province by identifying and training additional focal points. From November 2012 to January 2013, a total of six joint protection teams were deployed in South Kivu, North Kivu and Orientale Provinces to protect civilians under imminent threat.

Mission deployment and provision of support to operations by the Congolese armed forces against armed groups

36. MONUSCO continued to support the Congolese armed forces in confronting and containing the M23 rebellion in North Kivu at both the command level in Kinshasa and the tactical operational zone level in the field. The support was provided in strict compliance with the human rights due diligence policy on United Nations support to non-United Nations security forces.

37. On 15 November, M23 launched a major offensive against the Congolese armed forces in North Kivu. During the battles that unfolded at Kibumba, Kibati, Munigi and up until the entry of M23 into Goma, MONUSCO forces were alongside FARDC and in some cases by themselves at the front. MONUSCO robustly supported FARDC, including through direct military engagement. MONUSCO launched 18 attack helicopter missions firing 620 rockets, four missiles and 492 rounds of 30-mm ammunition. On the ground, infantry support vehicles of the Mission fired some 800 30-mm rounds and North Kivu Brigade fired approximately 4,000 rounds of small arms ammunition in contact with the attacking forces seeking to advance on Goma. […]

39. In South Kivu, MONUSCO built up its forces in and around Bukavu to prevent further advances of M23 southwards, notably around the airfield at Kavumu, where the attack helicopters of the Mission had been redeployed. MONUSCO coordinated defensive plans with FARDC and provided advice and training to FARDC units deployed in subsequent defensive positions in both North and South Kivu in order to help improve their capacity to hold ground and to counter any further attempts by M23 to undertake renewed offensive operations and threaten population centres and civilians.

40. Operations elsewhere in the country in support of FARDC continued. In Orientale Province, Operation Reassurance, targeting LRA, was launched in December, while operations in Ituri in support of FARDC against FRPI continued. Furthermore, MONUSCO implemented a series of quick-impact retraining and re-equipping programmes, with the aim of bolstering the operational capabilities of FARDC. However, during the reporting period, the Government did not seek MONUSCO support for FARDC operations against Mayi-Mayi groups in central Katanga.

41. On 6 January, a MONUSCO armoured personnel carrier based at the mobile operating base in Mambasa supported FARDC with heavy machine gun fire and jointly pushed back the several hundred Mayi-Mayi Simba combatants who had entered Mambasa town the previous day and caused FARDC to temporarily withdraw from the town. A MONUSCO helicopter from Bunia replenished FARDC small arms ammunition and rockets and evacuated 14 injured FARDC soldiers. [...]

Human rights

45. Effects of M23 military activities in North Kivu continued to be at the core of human rights concerns. A high number of allegations of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by M23 combatants were reported during the period under review, in particular in November 2012. The violations included killing, wounding, forced displacement, extensive looting and rape of civilians, including minors. Serious human rights violations were also committed by elements of FARDC while they were retreating from Goma on 20 November. Other armed groups, such as the Mayi-Mayi Raia Mutomboki, FDLR, the Mayi-Mayi Simba/ Lumumba and the Mayi-Mayi Gédéon, continued to take advantage of the security void left by the redeployed FARDC units to areas affected by the M23 rebellion. They launched violent attacks in various areas, and committed serious human rights violations against the civilian population.

46. Despite the difficulties encountered in verifying a high number of allegations, mainly due to security constraints and witness/victim protection concerns, MONUSCO was able to confirm that M23 was responsible for serious human rights violations in several parts of Rutshuru territory, Goma, Sake and surrounding areas, including the killing and wounding of civilians, abductions, rapes and widespread lootings. In line with its protection mandate, the Mission provided various forms of assistance to several categories of civilians most at risk from M23 threats. In North and South Kivu, at least 19 human rights defenders and three journalists received direct threats from M23 elements, mostly for having spoken out against the group and resisting recruitment or defying orders.

47. The escape of all detainees of Goma prison on 20 November and the prison break of 300 detainees in Butembo prison on 13 January, as well as the looting and destruction of judicial files at the North Kivu military court in Goma by M23 combatants late in November, represent a major setback in the fight against impunity and a threat to the security of civilians.

48. As a result of several mobile court hearings held during the reporting period with the support of MONUSCO, three alleged Mayi-Mayi Simba combatants were convicted by the Ituri military garrison tribunal to sentences ranging from 20 years to life imprisonment for participation in an insurrectional movement, illegal detention of weapons of war and/or crimes against humanity involving rape, looting and murder. MONUSCO continues to advocate for the arrest and trial of the leader of the group, Captain Morgan, who is still at large. Slow progress was registered with regard to the trial in the case of the murder of Congolese human rights defender Floribert Chebeya and the enforced disappearance of his driver, Fidèle Bazana. Alleged perpetrators of the human rights violations committed in Kinshasa in the scope of the November 2011 elections, mainly elements of the defence and security forces, including of the Republican Guard, have yet to be arrested. [...]

Sexual violence

50. Sexual violence continued to be of high concern. Nationwide, in November and December, MONUSCO recorded cases of sexual violence involving at least 333 women, including 70 girls, that were allegedly committed by armed groups and national security forces. In Orientale Province, in November, at least 66 women, including four minors, were reportedly raped by Mayi-Mayi Simba/Lumumba combatants in Mambasa territory. The victims were reportedly targeted during attacks on villages for their perceived collaboration with FARDC during operations against Mayi-Mayi Simba, aimed at chasing away the rebels from the mining area in Southern Mambasa. The number of cases may be far higher. Investigations into these violations are ongoing.

51. The armed forces were also responsible for serious human rights violations. In South Kivu, at least 126 women, including 24 girls, were reportedly victims of sexual violence by FARDC soldiers in Minova and its surrounding villages, in Kalehe territory, from 20 to 22 November. A total of 11 FARDC elements had been arrested so far and were awaiting trial. [...]

Children and armed conflict

53. An alarming number of reports of grave violations of children’s rights were documented, including killing and maiming, child recruitment, sexual violence and occupation of schools. As at 31 December, MONUSCO had documented 41 child casualties as a direct result of violent conflict. Those casualties included four children who had been killed and 37 others who had been injured. The majority of victims had been killed or wounded by stray bullets or shrapnel during armed clashes between FARDC and M23 from 19 to 22 November in and around Goma.

54. Child recruitment by armed groups also increased dramatically. Cases were documented of 210 children, including 187 boys and 23 girls, who had been recruited or who had separated or escaped from armed groups. Of particular concern are ongoing reports of child recruitment by M23 in both Rwandan and Congolese territory. A total of 21 boys, including at least 7 Rwandan nationals associated with M23 in North Kivu, were interviewed by MONUSCO during the reporting period, bringing the total number of children associated with M23 documented by MONUSCO to 66. Their testimonies detailed widespread, ongoing and systematic underage recruitment on Congolese and Rwandan territory, as well as other violations, such as the killing and maiming of children within the ranks of M23. The 11 children arrested by Congolese security forces on allegations of association with M23 were released through advocacy by MONUSCO after having being detained for between two and six months. MONUSCO remains concerned by the prolonged detention and reports of ill-treatment of the children during detention. In addition, in Goma, MONUSCO is providing protection to transit centres hosting children formerly associated with armed groups through daily patrolling.

55. Also in North and South Kivu, at least 42 primary and secondary schools were occupied and damaged by the Congolese armed forces. MONUSCO advocacy with the FARDC hierarchy resulted in the withdrawal of all troops from educational institutions. However, six schools in the Kivus continued to be occupied and used as weapons depots. [...]

Illegal exploitation of natural resources

57. The centres de négoce (mining trading centres), established by the Government to ensure the traceability of minerals, were suspended on 18 December during a meeting of the partners due to two major obstacles. The first is the insecurity prevailing mainly in the mining sites around the Ndjingila and Itebero centres in Walikale territory due to the threats posed by the presence of Mayi-Mayi Raia Mutomboki and other armed groups and the FARDC military operations against them. The second stems from the rivalry between the holders of mining titles and artisanal miners affecting the opening of the centres of Rubaya, in North Kivu, and Mugogo, in South Kivu. Thousands of artisanal miners engage in illegal mining, as no official artisanal exploitation zones have been established to date in those areas. MONUSCO and the Ministry of Mines tried unsuccessfully to mediate between title holders and artisanal miners in order to attain special agreements aimed at recognizing the rights of the artisanal miners to exploit and process their production through the centres. All parties agreed that the operation of artisanal miners in concessions has legal, social and economic implications that need to be addressed during the current revision of the Mining Code in order to find long-term solutions.

58. Concurrently, MONUSCO continued to support the process of tagging minerals and validating mining sites in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo to determine if mines are directly or indirectly controlled by armed groups and if basic human rights standards are respected. Despite efforts by MONUSCO, the establishment of two joint teams to monitor the illegal trafficking of minerals continues to be delayed since 2009 owing to a lack of resources and capacity of the Commission nationale de lutte contre la fraude minière. In parallel, with donor support, MONUSCO initiated a training project for “mining police” units of the Congolese national police.

Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration/disarmament, demobilization, repatriation, resettlement and reintegration

59. The military activities of M23 severely constrained the participation of foreign and Congolese armed elements in the disarmament, demobilization, repatriation, resettlement and reintegration process. During the reporting period, 279 foreign combatants and dependants were repatriated, including seven children who were associated with armed groups and 176 dependants. With respect to FDLR, 80 combatants, two children associated with armed groups and 159 dependants were repatriated. […]

62. There is an increasing mixture of Congolese and foreign elements in both Congolese and foreign armed groups. Continued recruitments by foreign armed groups, including in their country of origin, remain a challenge. Overall, to minimize the threats posed by armed groups, disarmament, demobilization, repatriation, resettlement and reintegration efforts should be complemented by other stabilization initiatives. […]

Justice and correction institutions

69. In November, MONUSCO, in close coordination with military and civilian justice authorities, evacuated from Goma 40 military and civilian justice personnel who were at risk of retaliation from M23 due to ongoing investigations of serious crimes involving some M23 leaders. The crisis left Goma with a considerable vacuum in the criminal justice chain.

70. Some progress was achieved in the prosecution of serious crimes by the Congolese military justice through the assistance of prosecution support cells. As a result, the memorandum of understanding between the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and MONUSCO on modalities of assistance of the cells, which expired on 18 December, was renewed for another year. During the reporting period, the cells registered three additional requests, for a total of 28 official requests, from the military justice authorities for support in the prosecution and investigation of serious crimes, including war crimes. The cells also supported the holding of seven mobile court sessions, during which 30 judgements were rendered, including 13 related to sexual violence crimes.

[...]

C. UN okays first-ever intervention force for DR Congo

[Source: “UN okays first-ever intervention force for DR Congo”, in English news, 29 March 2013, available at : http://news.xinhuanet.com]

UNITED NATIONS, March 28 (Xinhua) -- The UN Security Council on Thursday unanimously approved an unprecedented offensive "intervention brigade" with a mandate to operate in the strife-torn eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

However, while the enabling resolution authorizes the first-ever offensive unit, of 2,500 troops, to go after rebels by itself or with government troops in the nation's resource-rich eastern section on "an exceptional basis and without creating a precedent" for UN Peacekeeping Operations, it insists on a "clear exit strategy" before it expires in one year.

The special unit will become part of the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO).

Its objective is to counter the "destabilizing activities of the March 23 Movement (M23) and other Congolese and foreign armed groups operating in the eastern Congo," for violations of international humanitarian law, including "patterns of rape and other forms of sexual violence in situations of armed conflict" and an "increasing number of internally displaced persons in and refugees from eastern DRC."

The United Nations says almost 2 million people have been displaced.

In addition to the M23, the resolution listed the Forces Democratiques de Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR), the Alliance des Patriotes pour un Congo libre et souverain (APCLS) and the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) in North Kivu, the Mayi-Mayi Gedeon and the Mayi-Mayi Kata-katanga in Katanga Province, the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) in Orientale Province.

Additionally, the resolution cited "Rwandan reports of attacks by the FDLR on Rwandan territory."

Rwanda, just east of the DRC, had been accused in the past of aiding rebel troops in the DRC, but it joined Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, DRC, Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), South Sudan, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda in signing on Feb. 24 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a UN-drafted peace and security cooperation framework agreement for the DRC.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon welcomed the council's resolution saying it will better enable the world organization in its implementation. The UN is a guarantor of the Addis Ababa accord along with the African Union (AU), the International Conference on the Great Lakes region (ICGLR) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Ban hopes strengthening of MONUSCO's mandate "will contribute to the restoration of state authority and long-term stability in the eastern DRC," his spokesman said. "He remains personally committed to helping bring peace and stability to the people of the DRC and the Great Lakes region and will keep working to ensure this remains a top priority for the international community."

UN Undersecretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations Herve Ladsous told reporters "The brigade will be out of the force of MONUSCO and operate as a single command. Of course that will require additional enablers including helicopters that we are presently mustering. At the same time we are working with the countries that will contribute to the setting up of this brigade."

He anticipated three battalions from South Africa, Tanzania, Malawi, an artillery company and Special Forces and engineering elements."

I do very much think that today can be a significant turning point in the handling of this crisis which the DRC has suffered for many years," Ladsous said. "At the end of the day, it is about putting an end to the suffering of millions of people."

Ambassador Li Baodong of China, spoke to the council after the vote."

China is seriously concerned about the worsening security and humanitarian situation in the east of the DRC and is deeply worried about the serious consequences this has on regional peace and security," he said. "We resolutely support the efforts made by the government of the DRC in maintaining national sovereignty, territorial integrity, security and stability and we commend the United Nations, African Union and the relevant regional organizations for their positive role in addressing the problems in eastern DRC."

"We hope that the MONUSCO will continue its efforts in communicating and coordinating with the government of the DRC and strictly abide by the mandate as conferred by the Council so as to make a greater contribution in helping DRC in achieving long-term security," he said.

"China believes that the peacekeeping principles of the UN, the three principles which include consent of the parties, impartiality, and non-use of force except in self-defense or in defense of the mandate, provide an important guarantee for the success of the UN peacekeeping operations," Li said, attaching " great importance to the request by DRC" and other regional organizations for deployment of the intervention brigade.

"China agrees to an exceptional case to the deployment of an intervention brigade within MONUSCO," he said. "Under the terms of this resolution, deployment of this intervention brigade doesn't constitute any precedent nor does it affect the United Nations' continued adherence to the peacekeeping principles."

Discussion

A. Classification of the situation

- How would you classify the situation between the DRC and the M23 movement? Is this an armed conflict? Under Article 3 common to the Geneva Convention? Under Protocol II? Does the fact that the M23 receives support from and recruits members in foreign countries internationalize the conflict? When would the IHL of international armed conflicts apply? Would M23 members then benefit of POW status? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; GC III, Art. 4; P II, Art. 1(1))

B. Status of the MONUSCO and implications on the qualification of the conflict

-

- (Document B, para. 37) May peacekeeping forces be parties to an armed conflict? Did the MONUSCO become a party to the conflict when it supported FARDC through direct military engagement? Did this internationalize the conflict? Did MONUSCO become a party to the non-international armed conflict? Or should we describe the mission as an international police operation not covered by IHL?

- (Document B., para. 36) What is the mandate of the UN peacekeeping forces in this conflict? Does the nature of the mandate of a UN mission have an impact on the qualification of the conflict? Does the agreement of the host state to a UN mission have an impact on the classification of the conflict?

- Is the UN a Party to the Geneva Conventions and Protocols? Can the UN conceivably be a party to an international armed conflict in the sense of Article 2 common to the Conventions? To a non-international armed conflict? If so, which rules apply? All the rules of IHL? Only customary IHL?

- For the purpose of the applicability of IHL, can the UN peacekeeping forces be considered as armed forces of the contributing states (which are Parties to the Conventions), and can any hostile act be considered an armed conflict between those states and the opposing party?

-

- How would you assess the argument that IHL cannot formally apply to UN operations because such operations are not armed conflicts between equal partners but law enforcement actions by the international community authorized by the Security Council representing international legality, and that they aim not to make war, but to enforce peace?

- Why might the UN and its Member states not want to recognize the de jure applicability of IHL to UN operations?

-

- Assuming that IHL applies to the UN peacekeepers, does IHL apply to the situation in DRC? Is there an armed conflict? Is it an international or non-international armed conflict? Could the IHL of international armed conflicts apply even if there were no hostilities between UN forces and regular DRC armed forces? If only events like those described in either of the cases occurred, could the situation be qualified as an armed conflict? (GC IV, Art. 2)

- Assuming that IHL would apply to UN peacekeeping missions, could we consider that Goma is occupied by the UN forces? If so, can we apply the rules of occupation enshrined in Convention IV? Why or why not?

- What is the status of members of units of UN peacekeeping forces directly participating in the hostilities against one party of a non-international armed conflict in support of the other party? Does M23 violate IHL or do its fighters even commit a war crime if they attack such peace-keepers? If some units are no longer civilians, do all members of MONUSCO lose protection as civilians?

- What is the status of the intervention force set up by the Security Council? Are its members still civilians if they use force against the M23 to defend their mandate? Does this force respect the principles of consent of the parties, impartiality, and non-use of force except in self-defense or in defense of the mandate? Why does the Chinese ambassador insist that this is not a precedent? Should it be a precedent for future UN interventions in armed conflicts?

C. Violations of IHL and international human rights law

- Are human rights defenders and journalists lawful targets under IHL? If they denounce the activities of the armed groups? If they incite civilians to participate in hostilities and resist the armed groups? Is incitement to participate in hostilities itself a direct participation in hostilities? Is spreading propaganda an act of direct participation in hostilities? (P I, Arts 48, 50-51; P II, Art. 13(2); see Document, ICRC, Interpretive Guidance on the Notion of Direct Participation in Hostilities)

- Is rape prohibited under IHL? Even if the victim is a combatant? Even if the victim does not belong to the enemy? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; GC I-IV, Arts 50-51-130-147; GC IV, Art. 27(2); P I, Arts. 75(2) and 76(1); P II, Art. 4(2)(a) and (e); CIHL Rules 90, 91 and 93)

-

- Are children allowed to voluntarily join military forces under IHL? Does IHL differentiate between children who willingly took up weapons and children who have been forced? (P I, Art. 77(2) and (3); P II, Art. 4(3)(c) and (d); ICC Statute, Arts 8(2)(b)(xxvi) and 8(2)(e)(vii))

- May children be targeted when they directly participate in hostilities? (P I, Art. 77; P II, Art. 4(3); See 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict; ICC Statute, Art. 8)

- Does exploitation of natural resources by armed groups constitute a violation of IHL? Does it constitute, in all or some circumstances, pillage as prohibited by IHL? Even if done by artisanal miners? Could the exploitation of natural resources by the government ever constitute pillage under IHL? (P II, Art. 4(2)(g); ICC Statute, Art. 8(2)(e)(v) and (xii))

- Is the occupation of schools and their use as weapons depots lawful under IHL? If so used, is it lawful to attack these schools? (P I, Arts 48, 52(2) and 58; P II, Art. 13; CIHL, Rules 7, 22 and 24)

- Is the UN responsible for violations of IHL by Congolese governmental armed forces because it supports their fighting against their adversaries? If not, under what circumstances would they be responsible? How should the UN react to violations of IHL committed by forces it supports?