Mali, Conduct of Hostilities

Case prepared by Ms. Anaïs Maroonian, Master student at the Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva, under the supervision of Professor Marco Sassòli and Ms. Gaetane Cornet, research assistant.

N.B. As per the disclaimer, neither the ICRC nor the authors can be identified with the opinions expressed in the Cases and Documents. Some cases even come to solutions that clearly violate IHL. They are nevertheless worthy of discussion, if only to raise a challenge to display more humanity in armed conflicts. Similarly, in some of the texts used in the case studies, the facts may not always be proven; nevertheless, they have been selected because they highlight interesting IHL issues and are thus published for didactic purposes.

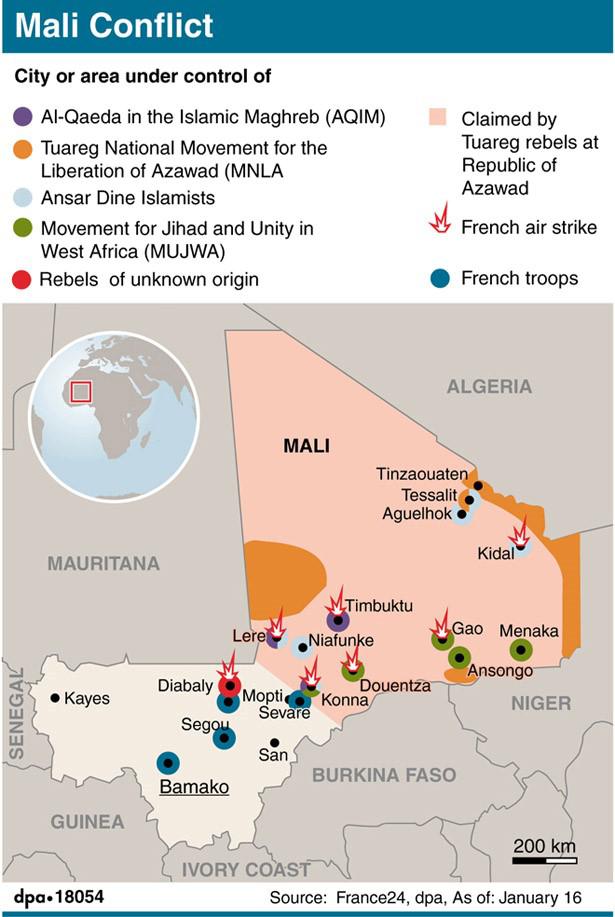

[Source: A Map of the Bewildering Mali Conflict, 16 January 2013; available at : http://www.theatlantic.com]

A. ICC, Situation in Mali, Article 53(1) Report

[Source: “Situation in Mali, Article 53(1) Report”, International Criminal Court, 16 January 2013; available at : http://www.icc-cpi.int]

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Article 53 criteria

1. [...] This report is based on information gathered by the Office [of the Prosecutor] from January until December 2012.

Procedural History

2. On 18 July 2012, the Malian Government referred “the Situation in Mali since January 2012” to the ICC.

Contextual background

3. As of around 17 January 2012, an ongoing non-international armed conflict continued in the territory of Mali between the government forces and different organized armed groups, particularly the Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, MNLA), al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Dine and the Mouvement pour l’unicité et le jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, MUJAO) and ‘Arab militias’, as well as between these armed groups themselves absent the involvement of government forces.

4. The armed conflict in Mali can be separated into two phases. The first phase began on 17 January 2012 with the attack by MNLA on the Malian Forces military base in Menaka (Gao region). This phase ended on 1 April 2012 when the Malian Armed Forces withdrew from the north. The second phase commenced immediately when non-State armed groups seized control of the North. This phase of the conflict is characterized primarily by armed clashes between the different armed groups, trying to gain exclusive control over the territory in the North, as well as by sporadic attempts by governmental forces to combat such armed groups and retake territorial control. (...)

II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY

15. The Office has been analysing the situation in Mali since violence erupted in northern Mali on or about 17 January 2012.

16. On 24 April 2012, the Office issued a public statement recalling that Mali is a State Party to the Rome Statute, and that the Court has jurisdiction over possible war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide that may be committed on the territory of Mali or by Malian nationals as of 1 July 2002.

17. On 30 May 2012, the Malian Cabinet made a public decision to refer crimes committed since January 2012 by MNLA, AQIM, Ansar Dine, and other armed groups in the regions of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu to the ICC. The Cabinet further stated that this situation has led to the withdrawal of the services of the administration of justice, making it impossible to deal with these cases before the competent national tribunals. [...]

19. On 5 July 2012, the Security Council adopted resolution 2056 based on Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, in which it stressed that attacks against buildings dedicated to religion or historic monuments can constitute violations of international law which may fall under Additional Protocol II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

20. On 7 July 2012, during a summit held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, the Contact Group on Mali of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) called for an ICC investigation into war crimes committed by rebels in the North of Mali, referring specifically to the destruction of historical monuments in Timbuktu and the arbitrary detention of persons. The Contact Group called upon the ICC “to initiate the necessary enquiries in order to identify the perpetrators of these war crimes and to initiate the necessary legal proceedings against them.”

21. On 18 July 2012, the Malian Government referred “the Situation in Mali since January 2012” to the ICC.

22. In August and October 2012, the OTP sent two missions to Mali for the purpose of verifying information in its possession.

III. CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND

Administration and population

[...]

25. In 2012, the Situation in Mali was marked by two main events: first, the emergence of a rebellion in the North on or around 17 January, which resulted in Northern Mali being seized by armed groups; and second a coup d’état by a military junta on 22 March, which led to the ousting of President TOURE shortly before Presidential elections could take place, originally scheduled for 29 April 2012.

The current rebellion

26. The rebellion started with an attack by the Tuareg rebel movement, the Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, MNLA) on a military base in the town of Menaka in the Gao region on 17 January 2012.

27. The Ansar Dine group as well as other armed groups joined, without necessarily coordinating operations between each other.

28. Between 30 March and 2 April 2012 the rebels advanced and took the main cities and military bases of Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu, forcing the Malian military to withdraw to the southern regions of Mali.

29. Armed confrontations between Ansar Dine and the MNLA have been reported since June 2012. The MNLA was eventually driven out of all urban centres and took up position outside the main cities. By the end of June 2012, Timbuktu and Kidal were under the firm control of Ansar Dine and Gao under the control of MUJAO. The presence of members from the Nigerian group “Boko Haram” has also been reported from Timbuktu.

The armed groups operating in the North

30. The MNLA is reported to be a secular nationalist Tuareg movement with political and military branches that operate in the Azawad desert in northern Mali. It was created in October/November 2011 in Timbuktu out of an already existing Tuareg opposition movement. The movement is primarily made up of former Tuareg fighters who have reportedly fought with the pro-Gaddafi forces and returned to their native lands at the end of the Libyan revolution in 2011.

31. Ansar Dine is regarded as a Tuareg jihadist salafist movement, aiming to impose Sharia law in all of Mali. This movement thus presents a radically different Tuareg nationalism from the one represented by the MNLA. While Ansar Dine was unable to reach an agreement on joining forces with the MNLA, it has links with different armed radical groups groups in northern Mali, including Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Mouvement pour l’unicité et le jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, MUJAO).

32. AQIM is a militant jihadi salafist organization that is considered to be the successor of the Algerian Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, GSPC) which emerged from the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA or Armed Islamic Group, AIG).

33. The MUJAO is reportedly a breakaway branch of AQIM. It published its first military statement in October 2011, declaring jihad in the largest sector of West Africa.

34. Other armed actors include the Malian Armed Forces as well as different local defence groups loyal to the Government that have recently regrouped under the Forces Patriotiques de Résistance (Patriotic Resistance Forces – FPR). The Armed Forces as well as the FPR are based in the southern regions of Mali.

The Coup d’Etat

35. On 22 March 2012, a week before presidential elections were scheduled to take place, a group of Malian soldiers, led by Captain Amadou Haya SANOGO, overthrew outgoing President TOURE. [...]

39. While the Burkinabe mediation is making contacts with armed groups in the North, preparations by AU and ECOWAS are underway to send an intervention force to Mali.

40. On 5 July and on 2 October 2012, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted Resolution 2056 and 2071 respectively, stressing that the perpetrators of human rights violations and international humanitarian law shall be held accountable.

41. On 20 December 2012, the UNSC adopted Resolution 2085 under Chapter VII of the UN Charter authorizing the deployment of the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA) to support national authorities to recover the North. The Resolution “calls upon AFISMA, consistent with its mandate, to support national and international efforts, including those of the International Criminal Court, to bring to justice perpetrators of serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law in Mali”. [...]

V. SUBJECT-MATTER JURISDICTION

46. For a crime to fall within the Court’s jurisdiction the crime must be one of the crimes set out in Article 5 of the Statute.

A. Alleged crimes

[...]

(a) Places of the alleged commission of the crimes

48. The majority of the alleged crimes have been committed in the regions of Gao and Timbuktu, and to a lesser extent Kidal (northern Mali). In addition, incidents of alleged crimes occurred in Bamako and Sévaré (southern Mali) in relation to infighting within the Malian army.

(b) Time period of the alleged commission of the crimes

49. Armed groups allegedly perpetrated crimes in the context of an ongoing non-international armed conflict which started on or around 17 January 2012.

50. The alleged execution of between 70 and 153 detainees at Aguelhok in January 2012 marked the peak of the killings in the first phase of the armed conflict from 17 January to 1 April 2012.

51. Incidents of looting and rape (up to 90 cases of rape or attempted rape) were mostly reported at the end of March/beginning of April when armed groups took control of the northern regions. The imposition of severe punishments and the destruction of religious buildings in Timbuktu and other areas in the North followed.

52. Separately incidents of torture and enforced disappearances were reported in the context of the military coup around 21-22 March 2012 and a counter-coup attempt on 30 April/1 May 2012.

(c) Persons or groups involved

53. The alleged crimes committed in the context of the armed conflict are mostly attributed to armed groups such as MNLA, Ansar Dine, AQIM, MUJAO and various militias.

54. Alleged crimes committed in the Southern part of Mali in the context of infighting within the Malian army are attributed to members or supporters of the (ex-) junta.

B. Legal Analysis

1. War crimes

(a) Contextual elements of war crimes

55. Article 8 of the Rome Statute requires the existence of an armed conflict. As stated by the Pre-Trial Chamber II, “[a]n armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between States or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups or between such groups within a State.”

56. A non-international armed conflict is characterised “by the outbreak of armed hostilities to a certain level of intensity, exceeding that of internal disturbances and tensions, such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence or other acts of a similar nature, and which takes place within the confines of a State territory. The hostilities may break out (i) between government authorities and organized dissident armed groups or (ii) between such groups.”

57. Thus, in order to distinguish an armed conflict from less serious forms of violence, such as internal disturbances and tensions, riots or acts of banditry, the armed confrontation must reach (1) a minimum level of intensity and (2) the parties involved in the conflict must show a minimum of organization.

58. As of around 17 January 2012, there has been an ongoing non-international armed conflict in the territory of Mali between the government forces and different organized armed groups, particularly MNLA, AQIM, Ansar Dine and MUJAO and ‘Arab militias’, as well as between these armed groups without the involvement of government forces. As discussed below, the required threshold of the level of intensity and the level of organization of parties to the conflict necessary for the violence to be qualified as an armed conflict of non-international character both appear to be met.

Level of intensity

17 January 2012 – 1 April 2012

59. The rebel offensive started in the north of Mali on or around 17 January 2012, when MNLA members reportedly attacked a military base in the town of Menaka in the Gao region but were pushed back by army reinforcements.

60. Hostilities spread to the towns of Aguelhok and Tessalit in the Kidal region when the rebels attacked army positions. By the end of that week, the army claimed that 35 attackers and a member of the Malian Armed Forces had died in fighting around the town of Aguelhok, while 10 attackers and a member of the Malian Armed Forces died in the town of Tessalit. A MNLA spokesman claimed that the Touaregs had killed 30 to 40 soldiers.

61. On 31 January 2012, MNLA rebels attacked Menaka again and took control of the town, after Malian Forces had withdrawn from their positions.

62. Fighting has been particularly heavy around the garrison town of Tessalit, close to the Algerian border. A major counter offensive was launched by the Malian Armed Forces on 14 February 2012. “Hundreds” are reported to have died, 50 rebels allegedly arrested and 70 vehicles destroyed. However, by 11 March, the MNLA eventually took control of the town. According to Jeune Afrique, Ansar Dine forces were also involved in the battle for Tessalit.

63. During a three-day offensive between 30 March and 1 April 2012, the MNLA further seized the three cities of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu, after the army withdrew from their positions in these areas. The Malian army regrouped in the southern city of Mopti.

64. Since the beginning of the rebellion in January 2012, clashes have also taken place between the Ganda Izo militia and the MNLA. Among those reportedly killed was Ganda Izo’s leader Amadou Diallo, with five of his men.

65. On 11 March Mauritanian Forces launched an air strike on an alleged AQIM convoy in Toual, outside Timbuktu. In early June 2012, Mali and Mauritania agreed to lead a joint military operation to fight AQIM. Therefore, the involvement of Mauritania does not change the non-international character of the armed conflict.

66. According to UN OCHA, by 22 February, more than 120,000 persons had been displaced by the conflict, including 60,000 internally and an equal number to neighboring countries.

1 April 2012 – present

67. Immediately after the Malian government forces withdrew, in-fighting between the MNLA and Ansar Dine started. On 2 April 2012 Ansar Dine took control of Timbuktu from the MNLA.

68. The MNLA clashed with Ansar Dine again on 7 June 2012 in Kidal and on 13 June 2012 in Timbuktu.

69. On 27 June 2012, the MNLA also clashed with MUJAO in Gao when 20 fighters were killed, including MNLA fighters.

70. Finally, on 11 July 2012 the MNLA was reportedly driven out from their last stronghold in Ansongo by MUJAO and Ansar Dine forces.

71. In accordance with a bilateral agreement between two states, Malian Forces carried out joint operations with the Mauritanian Army during the month of July in order to fight AQIM. Reportedly, after three weeks of heavy fighting in a joint “Operation Benkan”, Mauritanian and Malian Forces regained control of the city of Wagadou on 17 July 2012.

72. The military operations in the North continued when on 1 September 2012, MUJAO seized the central Malian town of Douentza.

73. On 16-17 November 2012, fighting broke out again between the MNLA and MUJAO in Ansongo, south of Gao and in Menaka, east of Gao in an unsuccessful attempt by the MNLA to retake Gao.MUJAO received reinforcements from AQIM.

74. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as at 1 November 2012, a total of 412,000 persons had been forced to flee their homes. This figure includes some 208,000 refugees who are currently hosted in Algeria, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mauritania, the Niger and Togo.

75. On 5 July 2012, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2056 (2012) on Mali under Chapter VII, “reiterating its strong condemnation of the attacks initiated and carried out by rebel groups against Malian Armed Forces and civilians”. The UN Security Council also addressed the issue of the worsening of the humanitarian situation in Mali as well as the increasing number of displaced persons and refugees.

Level of organization of parties

76. Malian Armed Forces: The Malian Armed Forces constitute a conventional army with clear lines of command and control. The strength of the active Malian armed forces is assessed in 2011 to be at 12,150 – 15,150.

77. MNLA: The MNLA is an armed group composed of around 10,000 fighters, which operates under the responsible command of Bilal Aq Cherif.

78. The MNLA showed the ability to plan and carry out military operations for a prolonged period of time when engaged in recurrent armed clashes against the Malian Armed Forces in the period from January through end of March 2012.

79. AQIM: AQIM is an armed group based in Southern Algeria with reportedly 4 military zones and a comprehensive organizational structure. Northern Mali is included in the ‘Sahara military zone’. The organization’s leadership is composed of the Emir, the council of notables, and heads of committees and organs. These organs constitute what is known as the Shura Council responsible for coordination between different levels of leadership. The strength of the active forces of AQIM was estimated at between 400- 800 fighters in 2010.

80. AQIM is divided into regional and central military units, or “brigades” called Katiba, each headed by a commander. The 5 central brigades report directly to the Emir of AQIM.

81. Ansar Dine: Ansar Dine is an armed group under the responsible command of Iyad Aq Ghali mainly present in Kidal. The group reportedly includes up to 300 fighters trained in camps in Kidal, Gao and Mopti. Ansar Dine has also moved to Timbuktu, as shown by its alleged involvement in the destruction of shrines and clashes with the MNLA in this city. According to open sources, Ansar Dine is able to procure, transport and distribute arms since these weapons have reportedly come from Libya and transited via Algeria.

82. The Ansar Dine leadership is able to control and govern parts of the territory through local councils established in towns that fell under its control. Additionally, the group reportedly set up a specialized police force in Timbuktu in order to enforce the Sharia law.

83. MUJAO: MUJAO has been reportedly founded and is led by Sultan Ould Badi together with AQIM’s former members Hammad Ould Mohamed Khair and Abou QoumQoum. There is little information about the actual strength of MUJAO, but it was assessed to be around 300 fighters. The movement announced its participation in the rebellion in the North. MUJAO controls a military camp in Gao and the towns of Douentza, Gao, Menaka, Ansongo and Gourma. This group has engaged in joint military operations elsewhere in the North with Ansar Dine.

Geographical and temporal scope of the armed conflict

84. As the International Criminal Tribunal of the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has held, “the temporal and geographical scope of both internal and international armed conflicts extended beyond the exact time and place of hostilities.”

85. Geographical scope: Even though the armed hostilities between parties to the conflict took place mainly in the north of the country, the geographical scope of the armed conflict extends to the entire territory of Mali.

86. Temporal scope: The armed conflict started on or around 17 January 2012 and is ongoing, since no peace settlement has been reached at the time of writing. [...]

(b) Underlying acts constituting war crimes

(i) Murder pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(i)

89. The actus reus of the crime of murder pursuant to Article (8)(2)(c)(i) requires the perpetrator killing one or more persons, and that such person or persons were either hors de combat, or were civilians, medical personnel, or religious personnel taking no active part in the hostilities

Alleged conduct by armed groups

The 24 January 2012 Aguelhok incident

90. The Malian government and the Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l’Homme (FIDH) allege that on 24 January 2012 the MNLA and/or other unspecified “armed groups” attacked the military camp in Aguelhok, detained and executed up to 153 Malian soldiers

91. The information available indicates that thereafter, during an organized search for the survivors of the attack, between 70 and 153 members of the Malian Armed Forces were hors de combat by detention, having been captured by members of the MNLA and possibly other groups.

92. They were allegedly tortured and/or murdered, some by the slitting of their throats, mutilation and disemboweling, while others were allegedly shot.

[...]

Other incidents of killings

94. Other information available on the alleged crime of killings relate to the stoning to death of an unmarried couple and the public execution of a member of MNLA. [...]

Alleged conduct by government forces

96. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that on 2 April 2012, Malian government soldiers in Sévaré (570 km from Gao) detained and executed at least 4 Tuareg members of the Malian security services. According to FIDH and Amnesty International, on 18 April 2012, Malian soldiers allegedly killed 3 unarmed persons accused of spying for the MNLA in Sévaré. At this stage, the information is insufficient to establish whether these incidents amount to the war crime of murder.

97. During the night of 8-9 September 2012, 16 unarmed Muslim preachers were reportedly shot dead by the Malian army at an army checkpoint while they were on their way to Bamako.[...]

(ii) Mutilation, cruel treatment and torture pursuant to Article (8)(2)(c)(i)

98. The actus reus of the war crime of mutilation pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(i) requires that the perpetrator subjected one or more persons to mutilation, in particular by permanently disabling or removing an organ or appendage.

99. The actus reus of the war crime of cruel treatment pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(i) requires that the perpetrator inflicted severe physical or mental pain or suffering upon one or more persons. The actus reus of the war crimes of torture requires an additional element, that is, that the perpetrator inflicted the pain or suffering for such purposes as obtaining information or a confession, punishment, intimidation or coercion or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.

100. The persons subjected to the conduct must be either combatants hors de combat, or were civilians, medical personnel or religious personnel taking no active part in hostilities.

101. HRW reported at least eight amputations imposed by armed groups in the North as punishments against persons accused of theft. Further, on 20 June 2012, an unmarried couple was punished with 100 lashes each in Timbuktu by armed groups. [...]

(iii) The passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(iv)

103. The actus reus of the war crime of sentencing or execution without due process pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(iv) requires that the perpetrator pass a sentence or carry out an execution of one or more persons who were either combatants hors de combat, civilians, medical personnel or religious personnel taking no active part in hostilities; and that the passing of the sentence or execution is carried out without previous judgement pronounced by a “regularly constituted” court, that is, a court which affords the essential guarantees of independence and impartiality, and the other judicial guarantees generally recognized as indispensable under international law.

104. Based on the information available, there seem to exist two categories of cases of imposing sentences on the civilian population and hors de combat in detention by the armed groups in Mali in the North, particularly in the regions of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. The first includes cases where the accused are brought before a panel of judges for a trial. Following the conclusion of the trial, sentences are imposed by judges and subsequently enforced by members of armed groups. The second includes cases where persons are punished by members of armed groups for an alleged conduct without previous trial.

105. With respect to the first category of cases, no lawyers are involved in the process. Most of the sentences, including floggings and amputations, are allegedly carried out by the police created by armed groups.

106. Reportedly, many of the punishments were carried out in public.

107. A number of incidents falling under the second category of cases have been reported by open sources. There are indications that the sentences are imposed arbitrarily by armed groups or by a panel of judges which did not afford the essential guarantees of independence and impartiality, or other judicial guarantees generally recognized as indispensable under international law.

108. The information currently available provides a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes of sentencing or execution without due process pursuant to Article 8(2)(c)(iv) were committed by armed groups in northern Mali. [...]

(v) Pillage pursuant to Article 8(2)(e)(v)

114. The war crime of pillage under Article 8(2)(e)(v) of the Statute requires that the perpetrator appropriated certain property without the consent of the owner, with the intent to deprive him or her of the property and to appropriate it for private or personal use.

115. According to the Malian government, AI, HRW and FIDH, the takeover of the large cities in the north of Mali, including Gao and Timbuktu, by armed groups at the end of March/beginning of April 2012 was accompanied by systematic looting and destruction of banks, shops, food reserves, as well as public buildings, hospitals, schools and places of worship, offices of international organizations, and residences of high-level civil servants, members of the Malian security services, and certain economic personalities. [...]

(vi) Rape pursuant to Article 8(2)(e)(vi)

117. The actus reus of the crime of rape pursuant to Article 8(2)(e)(vi) requires the perpetrator to invade the body of a person by conduct resulting in penetration, however slight, of any part of the body of the victim or of the perpetrator with a sexual organ, or of the anal or genital opening of the victim with any object or any other part of the body. Moreover, the actus reus requires that the invasion was committed by force, or by threat of force or coercion, such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power, against such person or another person, or by taking advantage of a coercive environment, or the invasion was committed against a person incapable of giving genuine consent.

118. FIDH claims that following the takeover of the North, including Gao and Timbuktu, more than 50 cases of rape or attempted rape were recorded, mostly in the period from March to May 2012.115 Cases of rape were reported in Gao, Timbuktu, Niafounke, villages around Dire, and in the Menaka region.

119. The information available provides a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes of rape pursuant to Article 8(2)(e)(vi) were committed.

(vii) Using, conscripting and enlisting children pursuant to Article 8(2)(e)(vii)

120. The actus reus of the crime of using, conscripting and enlisting children consists in the fact that the perpetrator conscripted or enlisted one or more persons into an armed force or groups or used one or more persons to participate actively in hostilities; and that such person or persons were under the age of 15 years old.

121. AI claims to have collected statements indicating the presence of child soldiers within the ranks of armed groups operating in Mali.

122. HRW reports to have identified 18 places where witnesses reported that new recruits including children were being trained, including military bases and schools.

123. According to UNICEF, as of 6 July 2012, at least 175 boys aged 12-18 were recruited into “armed groups” in Mali. The Malian Coalition of Child Rights, an umbrella organization of 78 Malian and international associations, spoke in early August 2012 of “several hundred children aged between nine and 17 within the ranks of the armed groups.”

124. The Office will continue to seek further information on these allegations. [...]

CONCLUSION ON SUBJECT-MATTER JURISDICTION

133. The information available indicates that there is a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes have been committed in the context of a non-international armed conflict in Mali since around 17 January 2012, namely: (1) murder constituting war crime under Article 8(2)(c)(i); (2) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions under Article 8(2)(c)(iv); (3) mutilation, cruel treatment and torture under to Article 8(2)(c)(i); (5) pillaging under Article 8(2)(e)(v); and (6) rape under Article 8(2)(e)(vi). This assessment is provisional in nature for purpose of meeting the requirements of article 53(1)(a). It is therefore not binding for the purpose of any future investigations. [...]

VIII. CONCLUSION

173. The information available provides a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes have been committed in the context of the Situation in Mali since January 2012 [...].

174. Since no national proceedings are pending in Mali or any other State against individuals who appear to bear the greatest responsibility for the most serious crimes committed in Mali, the Office has determined that the potential cases that would likely arise from an investigation into the situation would be admissible. Such cases, moreover, appear to be grave enough to warrant further action by the Court.

175. Since there are no substantial reasons to believe that such would not be in the interests of justice, the Prosecutor has decided to open an investigation into the Situation in Mali since January 2012.

B. France confirms Mali military intervention

[Source: “France confirms Mali military intervention” in BBC News, 11 January 2013, available at : http://www.bbc.co.uk]

President Francois Hollande says French troops are taking part in operations against Islamists in northern Mali.

French troops "have brought support this afternoon to Malian units to fight against terrorist elements", he said.

Armed groups, some linked to al-Qaeda, took control of northern Mali in April.

Mr Hollande said the intervention complied with international law, and had been agreed with Malian President Dioncounda Traore. A state of emergency has been declared across the country.

Mr Traore used a televised address on Friday to call on Malians to unite to "free every inch" of the country.

He said he was to launch a "powerful and massive riposte against our enemies" after he "called for and obtained France's air support within the framework of the international legality".

The militants said on Thursday that they had advanced further into government-controlled territory, taking the strategic central town of Konna.

The Islamists have sought to enforce an extreme interpretation of Islamic law.

Residents in nearby Mopti told the BBC they had seen French troops helping Malian forces prepare for a counter-offensive against the Islamists in Konna.

Mr Hollande said French military action had been decided on Friday morning and would last "as long as necessary".

"Mali is facing an assault by terrorist elements coming from the north whose brutality and fanaticism is known across the world," the French president said.

He said Mali's existence as a state was under threat, and referred to the need to protect its own population and 6,000 French citizens living there. France ruled Mali as a colony until 1960.

French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius said the aim of the operation was to stop Islamist militants advancing any further.

"We need to stop the terrorists' breakthrough, otherwise the whole of Mali will fall into their hands threatening all of Africa, and even Europe," he told reporters.

He confirmed that the French air force was involved in the operation, but gave no details.

France was previously believed to have about 100 elite troops in the region. It also has a military base in Chad.

At least seven French hostages are currently being held in the region, and Mr Fabius said France would "do everything" to save them.

British Foreign Secretary William Hague said on Twitter that the UK supported the French decision to help Mali's government against northern rebels.

The US and African Union have also expressed support for the mission.

Shortly after Mr Hollande spoke, the west African bloc Ecowas said it was authorising the immediate deployment of troops to Mali "to help the Malian army defend its territorial integrity", AFP news agency reported.

The Malian army said that as well as French troops, soldiers from Nigeria and Senegal were already in Mali – though Senegal later denied that it had any combat troops in the country, according to AFP.

The UN had previously approved plans to send some 3,000 African troops to Mali to recapture the north if no political solution could be found, but that intervention was not expected to happen until September.

Late on Thursday, an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council called for the rapid deployment of an African-led force.

The EU also said it would support such a mission, and speed up preparations for its own military training mission.

Discussion

A. Classification of the situation and applicable law

- (Doc. A and B)

- How would you classify the situation between the government and the different organized armed groups? Do you have to assess the existence of an armed conflict for each group separately or is the fact that one armed groups fulfills the conditions to be a party to a non-international armed conflict sufficient to apply IHL to the relations between the government and all the other armed groups, and between such groups? To conduct linked to the conflict by individuals not linked to any group? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; P II, Art. 1)

- How would you classify the situation between the government and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA)? Between the government and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)? Between the government and Ansar Dine? Between the government and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO)? Between the government and so called “Arab militias”? Between Ansar Dine and MNLA? Does Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions apply? Does Protocol II apply?

- Is the coup d’état in Mali governed by IHL? In the Prosecutor’s view? In your view?

- (Doc. A and B)

- When does a non-international armed conflict begin? Which conditions must be fulfilled for a situation to be qualified as a non-international armed conflict? Are they fulfilled in this case? (P II, Art. 1)

- Do all organized armed groups fulfill the conditions for the application of Protocol II?

- (Document A, para. 76) Was it necessary for the Prosecutor to analyze whether the Malian armed forces were sufficiently organized?

- Is it necessary for a rebel group to control territory in order for Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions to apply? In order to determine whether the group is sufficiently organized? In order to determine whether the group is a party to the conflict? (GC I-IV, Art. 3)

- Once the requisite level of intensity has been reached, until when does IHL apply? What happens if the level of intensity or the rebel group’s degree of organization drops below that threshold?

- Does the participation of the Mauritanian forces internationalize the conflict in Mali? Why? What about the French intervention? What is needed for a non-international armed conflict to become an international one? (GC I-IV, Art. 2(1))

B. Respect of IHL

- (Document A)

- Under which conditions does a person become a legitimate target in a non-international armed conflict? Were hors de combat Malian Armed Forces a legitimate target? Are armed forces protected in any way in an international armed conflict? In a non-international conflict? (P I, Art. 35; P II, Art. 13(3))

- Is the killing of the unmarried couple covered by IHL?

- Under IHL, is a member of the armed forces or of an armed group a legitimate target while he or she is not directly participating in hostilities? (see Document, ICRC, Interpretive Guidance on the Notion of Direct Participation in Hostilities)

- Does IHL of non-international armed conflicts prohibit the imposition of Sharia Law?

- Are hospitals protected against attacks in non-international armed conflicts? Are hospitals legitimate targets if they are used to treat wounded enemy soldiers? If they are used to stock ammunitions? Is it a war crime to attack a hospital during a non-international armed conflict? (P II, Art. 11; CIHL, Rule 28; ICC Statute, Art. 8(2)(e)(ii))

- Is pillage prohibited under IHL? In international armed conflicts? In non-international armed conflicts? Does it matter if the property belongs to the state or to private persons? (HR, Arts 28 and 47; GC IV, Art. 33(2) ; P II, Art. 4(2)(g); ICC Statute, Art. 8(2)(b)(xvi) and (e)(v))

C. Treatment of civilians

-

- Do the reported amputations as punishment of thieves violate IHL of non-international armed conflicts? What about the 100 lashes inflicted on the unmarried couple? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; P II, Arts 4 and 13; CIHL, Rule 91)

- Does torture constitute a violation of IHL? Is it a war crime? Even though the victim did not belong to the other party to the non-international armed conflict? What about arbitrary arrest and sentencing? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; GC I, Arts 12(2) and 50; GC II, Arts 12(2) and 51; GC III, Arts 17(4), 87(3), 89 and 130; GC IV, Arts 27, 31-32 and 147; P I, Art. 75(2); P II, Art. 4(2); CIHL, Rule 90; ICC Statute, Arts 8(2)(a)(ii) and (iii) and (c)(i))

-

- Is rape prohibited under IHL? Even if the victim does not belong to the enemy? (GC I-IV, Art. 3; GC I-IV, Arts 50-51-130-147; GC IV, Art. 27(2); P I, Arts. 75(2) and 76(1); P II, Art. 4(2)(a) and (e); CIHL Rules 90, 91 and 93)

- Is rape a war crime? What additional measures could help put an end to this practice? Would an additional international instrument be useful? What provisions should it contain? (GC IV, Art. 147, ICC Statute, Art. 8(2)(b)(xxii) and (e)(vi))

- Under IHL, does it matter whether the rape victim is a civilian, a combatant, a fighter, a militant sympathizer, or a terrorist?

- Is there any conceivable situation in which a rape committed in an armed conflict does not violate IHL?

- (Paras 120-124)

- How are children protected by IHL? In international armed conflicts? In non-international armed conflicts? (GC IV, Arts 14, 17, 23-24, 38(5), 50, 76, 89, 94; P I, Arts 70 and 77-78; P II, Arts 4(3) and 6(4))

- What are the specific rules concerning child recruitment? What kind of rules could increase their protection? (P I, Art. 77(2); P II, Art. 4(3)(c); UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Art. 38(3); ICC Statute, Art. 8(2)(b)(xxvi) and (e)(vii); Document, Optional Protocol to the CRC, Art. 2 and 4)

- Do children lose their protection against attacks when they directly participate in hostilities? If so, can they be targeted when they are engaged in any of the activities mentioned by the Report? Is there a contradiction between the notion of “direct participation in hostilities”, allowing targeting of persons directly involved in combat, and the purposes of the special protection granted to children by IHL? Should children be excluded from the notion of direct participation in hostilities? Would it be realistic to require from the parties to a conflict to not target children even when they are directly engaged in combat?

- Is the prohibition of recruitment of children under 15 into armed forces or of their use to participate actively in hostilities a customary rule of international law? (CIHL, Rules 136 and 137)

D. ICC Jurisdiction

- May Mali refer only acts committed by armed groups to the ICC, or must the ICC necessarily also establish jurisdiction over war crimes committed by Malian soldiers? By French forces? (ICC Statute, Art. 14)