I. Human Rights Council, Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lebanon - Paras 1 to 68

I. Human Rights Council, Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lebanon

N.B. As per the disclaimer, neither the ICRC nor the authors can be identified with the opinions expressed in the Cases and Documents. Some cases even come to solutions that clearly violate IHL. They are nevertheless worthy of discussion, if only to raise a challenge to display more humanity in armed conflicts. Similarly, in some of the texts used in the case studies, the facts may not always be proven; nevertheless, they have been selected because they highlight interesting IHL issues and are thus published for didactic purposes.

[Source: Human Rights Council, Report of Commission of Inquiry on Lebanon pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-2/1, A/HRC/3/2, 23 November 2006, available at

http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HR_in_armed_conflict.pdf, footnotes omitted]

Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lebanon

pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-2/1

[…]

I. INTRODUCTION

[…]

B. The conflict as addressed by the Commission’s mandate

1. Lebanon: profile and background

[…]

- During the 1980s Israel carried out frequent military operations, including shellings and air attacks, and undertook an extended occupation of southern Lebanon. The Hezbollah organization, as will be explained later, was created in the context of the Israeli occupation.

- Israel remained in control of Southern Lebanon until May 2000, when it withdrew its troops in compliance with Security Council resolutions 425 (1978) and 426 (1978).

[…]

- Despite the Israeli withdrawal, sporadic armed operations along the Israeli-Lebanese southern border continued to oppose the Israeli armed forces to Hezbollah militia, mainly on the grounds of Israel’s continued occupation of the Shab’a farms. The Shab’a farms area was occupied by Israel in 1967. In 1981, Israel decided to extend the application of Israeli law to the occupied Shab’a region. The Security Council, in resolution 497 (1981) of 17 December 1981, condemned this action and declared it “null and void and without international legal effect”. Lebanon considers the Shab’a farms as part of its territory, as indicated in the Memorandum of 12 May 2000 addressed to the Secretary-General on 12 May 2000. The Hezbollah leadership has pledged to continue opposing Israel as long as it continues its occupation of the Shab’a farms area. […]

[…]

- Hezbollah is a Shiite organization that began to take shape during the Lebanese civil war. It originated as a merger of several groups and associations that opposed and fought against the 1982 Israeli occupation of Lebanon. Hezbollah has grown to an organization active in the Lebanese political system and society, where it is represented in the Lebanese parliament and in the cabinet. It also operates its own armed wing, as well as radio and satellite television stations. It further funds and manages its own social development programmes.

- Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and after, Hezbollah’s raison d’être has been the continued occupation by Israel of Lebanese territory and the detention of Lebanese prisoners in Israel. The extent of the destruction and the difficult conditions that the Israeli occupation imposed on the Lebanese population, particularly the Shiite population living in south Lebanon, generated strong popular support for Hezbollah. […]

[…]

2. The July-August 2006 hostilities

- On 12 July 2006, a new incident between Hezbollah military wing and IDF led to an upward spiral of hostilities in Lebanon and Israel that resulted in a major armed confrontation. The situation began when Hezbollah fighters fired rockets at Israeli military positions and border villages while another Hezbollah unit crossed the Blue Line, killed eight Israeli soldiers and captured two.

- Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert described this capture as an action by the sovereign country of Lebanon that attacked Israel and promised a “very painful and far-reaching response.” Israel blamed the Government of Lebanon for the raid, as it was carried out from Lebanese territory and Hezbollah was part of the Government.

- In response, Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Siniora denied any knowledge of the raid and stated that he did not condone it. An emergency meeting of the Government of Lebanon reaffirmed this position. Furthermore, in a letter dated 13 July 2006 to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council, the Government of Lebanon declared that “[T]he Lebanese Government was not aware of the events that occurred and are occurring on the international Lebanese border” and that “[T]he Lebanese Government is not responsible for these events and does not endorse them.”

- From 13 July 2006, the IDF attacked Lebanon by air, sea and land. Israeli ground forces carried out a number of incursions on Lebanese territory. Israel’s chief of staff Dan Halutz stated that “if the soldiers are not returned, we will turn Lebanon’s clock back 20 years,” while the head of Israel’s Northern Command Udi Adam said, “this affair is between Israel and the State of Lebanon. Where to attack? Once it is inside Lebanon, everything is legitimate – not just southern Lebanon, not just the line of Hezbollah posts.” The Israeli Cabinet authorized “severe and harsh” retaliation on Lebanon.

- The Government of Lebanon decided on 27 July 2006 that it would extend its authority over its territory in an effort to ensure that there would not be any weapons or authority other than that of the Lebanese State.

- […] Lebanon frequently pleaded for the Security Council to call for an immediate, unconditional ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah.

- On 11 August 2006, the Security Council adopted resolution 1701 (2006) calling inter alia for a “full cessation of hostilities based upon, in particular, the immediate cessation by Hezbollah of all attacks and the immediate cessation by Israel of all offensive military operations, and emphasizing the need to address urgently the causes that have given rise to the current crisis, including by the unconditional release of the abducted Israeli soldiers.” On the same day, the Human Rights Council, meeting in special session, adopted resolution S-2/1, condemning Israeli violations of human rights and of international humanitarian law and calling for the establishment of the Commission of Inquiry.

- Both parties to the conflict agreed on a ceasefire, which took effect on 14 August 2006 at 0800 hours.

[…]

- The blockade was lifted on 6-7 September 2006. On 1 October, the Israeli army reported that it had completed its withdrawal from southern Lebanon, information that was confirmed by UNIFIL. […] The situation related to Shab’a Farms remained the same.

3. Qualification of the conflict

- […] [T]he two key issues that inherently arise are, (a) whether or not between 12 July and 14 August 2006 an armed conflict took place in Lebanon and in Israel, and if so, (b) who were the Parties to it.

- […] [I]t is well established in international humanitarian law that for the existence of an armed conflict the decisive element is the factual existence of the use of armed force. That aside, there is authority for the proposition that an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between States or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups or between such groups within a State. International humanitarian law applies as soon as an armed conflict arises and it binds all the parties thereto to fully comply with it. On the basis of the factual circumstances of the conduct of the hostilities that took place, including the intensity of the violence and the use of armed force, the Commission is of the view that the existence of an armed conflict during the relevant period has been sufficiently established.

[…]

- A particular characteristic and the sui generis nature of the conflict is that active hostilities only took place between Israel and Hezbollah fighters. The Commission found no indication that the Lebanese Armed Forces actively participated in the hostilities that ensued. For its part, IDF attacked the Lebanese Armed Forces and its assets (e.g. military airport at Qliat in northern Lebanon, all radar installations along the Lebanese coast, and the army barracks at Djamhour, 100 kilometres from the southern border with Israel.) A joint Security Force comprising the LAF and the Police offered no resistance to the IDF at Marjayoun on 10 August 2006.

- On the conflict, the position of the Government of Lebanon is that it was not responsible for and had no prior knowledge of the operation carried out by Hezbollah against an IDF patrol inside Israeli territory on 12 July 2006. This was orally confirmed by Prime Minister Siniora to the Commission when they met in Beirut on 25 September 2006. Lebanon has also stated that it disavowed and did not endorse that act. Furthermore, the Government of Lebanon has emphasized that it is the sole authority that decides on peace and war and the protection of the Lebanese people. It participated effectively in the negotiations leading to the adoption of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) accepted by both Israel and Lebanon. For its part, the Government of Israel has officially stated that responsibility lies with the Government of Lebanon, from whose territory these acts were launched into Israel, and that the belligerent act was the act of a sovereign State, Lebanon.

- It is the view of the Commission that hostilities were in actual fact and in the main only between the IDF and Hezbollah. The fact that the Lebanese Armed Forces did not take an active part in them neither denies the character of the conflict as a legally cognizable international armed conflict, nor does it negate that Israel, Lebanon and Hezbollah were parties to it. Regarding this, the Commission stressed three points.

- First, in Lebanon, Hezbollah is a legally recognized political party, whose members are both nationals and a constituent part of its population. It has duly elected representatives in the Parliament and is part of the Government. Therefore, it integrates and participates in the constitutional organs of the State.

- Secondly, for the public in Lebanon, resistance means Israeli occupation of Lebanese territory. The effective behaviour of Hezbollah in South Lebanon suggests an inferred link between the Government of Lebanon and Hezbollah in the latter’s assumed role over the years as a resistance movement against Israel’s occupation of Lebanese territory. In its military expression and in the light of international humanitarian law, Hezbollah constitutes an armed group, a militia, whose conduct and operations enter into the field of application of article 4, paragraph 2 (b), of the Third Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949. Seen from inside Lebanon and in the absence of the regular Lebanese Armed Forces in South Lebanon, Hezbollah constituted and is an expression of the resistance (‘mukawamah’) for the defence of the territory partly occupied. A government policy statement regarded the Lebanese resistance as a true and natural expression of the right of the Lebanese people in defending its territory and dignity by confronting the Israeli threat and aggression. In his address to the nation, on 18 August 2006, President Emile Lahoud paid tribute to the “National Resistance fighters”. Hezbollah had also assumed de facto State authority and control in South Lebanon in non-full implementation of Security Council resolutions 1559 (2004) and 1680 (2006), which, inter alia, had called for and required the disarmament of all armed groups, and had urged the strict respect of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and unity of Lebanon under the sole and exclusive authority of the Government of Lebanon throughout the country.

- Thirdly, the State of Lebanon was the subject of direct hostilities conducted by Israel, consisting of such acts, as an aerial and maritime blockade that commenced on 13 July 2006, until their full lifting on 6 and 8 September 2006, respectively; a widespread and systematic campaign of direct and other attacks throughout its territory against its civilian population and civilian objects, as well as massive destruction of its public infrastructure, utilities, and other economic assets; armed attacks on its Armed Forces; hostile acts of interference with its internal affairs, territorial integrity and unity and acts constituting temporary occupation of Lebanese villages and towns by IDF.

- That aside, a number of Lebanese high government authorities informed the Commission that they considered that, to the extent that Lebanon was a victim, and suffered the devastating effect of armed hostilities by Israel, it was a party to the conflict. In the words of the Minister of Justice: “un agressé peut être une partie d’un conflit”. Insofar as it is relevant and having regard to common article 2, paragraph 2, of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, international humanitarian law applies even in a situation, where for example the armed forces of a State party temporarily occupy the territory of another State, without meeting any resistance from the latter. On the same legal basis, it has been stated that the Geneva Conventions apply even where a State temporarily occupies another State without an exchange of fire having taken place or in a situation where the Occupying State encounters no military opposition whatsoever.

- The Commission considers that both Lebanon and Israel were parties to the conflict. They remain bound by the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and customary international humanitarian law existing at the time of the conflict. Hezbollah is equally bound by the same laws. For completeness, and as mentioned earlier, both Israel and Lebanon are parties to the main international human rights instruments, and they remain legally obliged to respect them.

- Moreover, while Hezbollah’s illegal action under international law of 12 July 2006 provoked an immediate violent reaction by Israel, it is clear that […] Israel’s military actions very quickly escalated from a riposte to a border incident into a general attack against the entire Lebanese territory. Israel’s response was considered by the Security Council in its resolution 1701(2006) as “offensive military operation”. These actions have the characteristics of an armed aggression, as defined by General Assembly resolution 3314 (XXIX).

- The fact that Israel considered Hezbollah a terrorist organisation and its fighters as terrorists does not influence the Commission’s qualification of the conflict. Several official declarations of the Government of Israel addressed Lebanon as assuming responsibility. IDF views its operations in Lebanon as an international armed conflict.

4. Applicable law

[…]

(a) International Humanitarian Law

- The basic corpus of international humanitarian law is applicable to the conflict, and both Israel and Lebanon are party to key international humanitarian law instruments. Israel is party to the four Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, but has not ratified Additional Protocol I or II on the protection of victims of armed conflict. In addition, Israel is party to the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of 14 May 1954 and its First Protocol (1954); the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects of 10 October 1980, as well as its Protocol I on non-detectable fragments (1980), Protocol II on prohibitions or restrictions on the use of mines, booby-traps and other devices (1980 and as amended on 3 May 1996), and Protocol IV on Blinding Laser Weapons (1995). Israel has neither ratified Protocol III on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Incendiary Weapons (1980), nor Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War (2003).

- Lebanon is party to the four Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 as well as Additional Protocols I and II relating to the protection of victims of armed conflicts. It is also party to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction (1972), and the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of 14 May 1954 and its First Protocol. Lebanon is not party to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects of 10 October 1980, nor to any of its Protocols.

- In addition to the international treaty obligations, rules of customary international human rights and humanitarian law bind States and other actors. In other words, all of the parties to the conflict are also subject to customary international humanitarian law. As a party to the conflict, Hezbollah is also bound to respect international humanitarian law and human rights.

- Serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law are regulated inter alia by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, as well as customary international law. Israel has signed but has not ratified the Statute. Lebanon has neither signed nor ratified the Statute.

[…]

Paras 76 to 208

II. THE FACTS AND LEGAL ANALYSIS

A. General approach

1. On the facts

[…]

- The 33-day conflict in Lebanon […] exacted a heavy human toll and damaged economic and social structures, as well as the environment. During the campaign, Israel’s Air Force flew more than 12,000 combat missions. Its Navy fired 2,500 shells, and its Army fired over 100,000 shells, destroying as a consequence large parts of the Lebanese civilian infrastructure, including roads, bridges and other ‘targets’ such as Beirut International Airport, ports, water and sewage treatment plants, electrical facilities, fuel stations, commercial structures, schools and hospitals, as well as private homes. According to Government of Lebanon figures, 30,000 homes were destroyed or damaged, 109 bridges and 137 roads (445,000 sq. km.) damaged, and 78 health facilities (dispensaries, health centres and hospitals) were seriously affected, with 2 hospitals destroyed. Furthermore, the Lebanese Government indicates that 900 commercial centres and factories were affected, as were 32 other “vital points” (airports, ports, water and sewage treatment, electrical plants). Over 789 cluster-bomb sites have been identified in southern Lebanon, and over one million bomblets have littered the region.

- The conflict resulted in 1,191 deaths and 4,409 injured. More than 900,000 people fled their homes. It was estimated that one third of the casualties and deaths were children.

- Israel also suffered serious casualties. Reports indicate that 43 civilians were killed, 997 were injured […], 6,000 homes were affected and 300,000 persons were displaced by Hezbollah’s attacks on Israeli towns in northern Israel.

[…]

B. Specific approach

1. Attacks on the civilian population and objects

- One of the most tragic facts of the conflict raises the question of direct and indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian objects and the violation of the right to life. […]

[…]

(a) Southern Lebanon

- Numerous villages throughout southern Lebanon suffered extensive bombing and shelling resulting in killings and massive displacement of civilians. Some villages were occupied by Israeli forces and suffered other kinds of damage. The Bekaa Valley also came under attack.

[…]

- In Taibe, the Commission gathered information on the occupation of part of the town by IDF, which set up sniper positions in the castle from which they could dominate the surrounding area; 136 houses and 2 schools were destroyed in Taibe.

- Witnesses explained to the Commission that most of the men in the village possessed guns. They stressed, however, that a distinction should be made between professional Hezbollah fighters and civilian militia volunteers from Amal and the Lebanese communist party who took up arms during the conflict. The volunteers were welcomed if they obeyed the Hezbollah rules but were otherwise ordered to leave the area. According to witnesses, Hezbollah did not fire rockets and mortars from within the village, or otherwise use it as a shield for its activities. Rather, Hezbollah used adjoining valleys, as well as caves and tunnels in the surrounding area from which to operate, and the surrounding countryside provided ample cover and security for their operations.

[…]

(b) South Beirut

- The Commission visited the South East suburbs of Beirut, which were heavily bombed from the earliest days until the last days of the conflict. This largely Shiite district of high-rise buildings is densely populated and a busy commercial centre, with hundreds of small shops and businesses. It was also a centre for Hezbollah activities in the city, including offices of the political headquarters of the organization, and its associated infrastructure, including Jihad al Bina, offices of parliamentarians, and the TV station Al-Manar. During the course of the conflict, many displaced persons from the South had sought refuge in the relative safety of this neighbourhood.

- […] Throughout the period of the conflict, nearly every day, IDF attacked and destroyed a handful of unoccupied multi-storey buildings. Nearly all of its 220,000 inhabitants have been forced to evacuate at the commencement of the hostilities. The presence of Hezbollah offices, political headquarters and supporters would not justify the targeting of civilians and civilian property as military objectives.

[…]

3. Attacks on infrastructure and other objects

- During the conflict major damage was inflicted on civilian infrastructure. According to the Government of Lebanon, 32 “vital points” were targeted by IDF. These include for example, the Port of Beirut where the radar was hit. The Commission was told by the Managing Director of the Port that the radar was used for ship navigation tracking, and not for military purposes. In addition, the modern lighthouse of Beirut was put out of use by a strike on 15 July. The airport of Beirut also suffered severe damage to its five runways and fuel tanks. This major destruction occurred during the first days of the conflict.

- A total of 109 bridges and 137 roads (445,000 sq. km.) were damaged during the conflict, including some bridges which had been repaired once already. The Commission heard evidence in Qana of the disproportionate use of weapons by IDF. In one incident, for example, IDF rockets were fired at a small bridge, three times with two rockets at a time, while the bridge was a simple construction used by shepherds.

- […] On many occasions this destruction occurred after humanitarian organizations had obtained a clearance from Israel to use these roads. In the same vein, the Commission was told that the evacuation of civilians was particularly hampered by the destruction of roads and bridges. […]

- Water facilities were destroyed or damaged during this conflict in many parts of the country. […] Numerous water towers had been hit by a direct fire weapon – probably a tank round. Most had a single round through them, sufficient to empty their content. Israeli soldiers were stationed in Froun, in order to control the water source. This led to a decrease of water distribution to the villages located in the Qada of Marjayoun, south of Taibe. In fact fears of lack of water were one of the reasons why civilians left their villages. In Beirut, in the Christian neighbourhood of Achrafieh, on 19 July, IDF bombed two engineering vehicles used to drill water.

- Transmission stations used by Lebanese television and radio were also the targets of bombing. A clear distinction has to be made between the Hezbollah-backed Al-Manar television station and others. While the first is clearly a tool used by Hezbollah in order to broadcast propaganda, nothing similar can be said regarding the others. IDF repeatedly targeted Al-Manar at the beginning of the conflict, notably its headquarters in the Beirut suburb of Haret-Hreik.

- In addition to Al-Manar, Future TV, New TV, and the Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation (LBCI) suffered damages to their infrastructure. The transmission and communication towers of Télé Lumière, a Christian television station founded in 1991, were damaged in six different locations.

- Regarding the Al-Manar TV station, Israel said that it has for many years served as the main tool for propaganda and incitement by Hezbollah, and has also helped the organization recruit people into its ranks. The Commission wishes to recall that the fact that al-Manar television broadcasts propaganda in support of Hezbollah’s attacks against Israel does not render it a legitimate military objective, unless it is used in a way that makes an “effective contribution to military action” and its destruction in the circumstances at the time offers “a definite military advantage.” The Commission points out that a TV station can be a legitimate target, for instance, if it called upon its audience to commit war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide. If it is merely disseminating propaganda to generate support for the war effort, it is not a legitimate target. The Commission was not provided with any evidence of this “effective contribution to military action”. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) condemned this attack in a press release of 14 July 2006, “warning that the attack follows a pattern of media targeting that threatens the lives of media staff, violates international law and endorses the use of violence to stifle dissident media”.

- With regard to attacks on other stations, nothing was said by the Israeli authorities and official reports only mention the destruction of the Hezbollah communications infrastructure. For these TV stations, links with Hezbollah could not be documented by the Israeli authorities and the Commission could not find any evidence in that regard. IFJ released a second communiqué on 24 July 2006 to condemn Israeli attacks on the media after one media worker of the Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation was killed in a bombing by IDF in Fatka and two others were wounded in a separate strike.

[…]

- Israel justified its attacks on the civilian infrastructure by invoking their hypothetical use by Hezbollah. For example, regarding Beirut International Airport, Israel said that it served Hezbollah to re-supply itself with weapons and ammunition. It also said it was a response to reports that it was the intention of Hezbollah to fly the kidnapped Israelis out of Lebanon. However, it underlined that in its operation at Beirut Airport IDF was careful not to damage the central facilities of the airport, including the radar and control towers, allowing the airport to continue to control international flights over its airspace. The same arguments were used regarding roads and bridges.

- The Commission appreciates that some infrastructure may have had “dual use” but this argument cannot be put forward for each individual object directly hit during this conflict. Even if some claims were true, the collateral harm to the Lebanese population caused by these attacks would have to be weighed against their military advantage, to make sure that the rule on proportionality was being observed. For example, cutting the roads between Tyre and Beirut for several days and preventing UNIFIL from putting up a provisional bridge cannot be justified by international humanitarian law. It jeopardized the lives of many civilians and prevented humanitarian assistance from reaching them. Injured persons needing to be transferred to hospitals north of Tyre could not get the medical care needed.

- By using this argument, IDF simply changed the status of all civilian objects by making them legitimate targets because they might be used by Hezbollah. The principle of distinction requires the Parties to the conflict to carefully assess the situation of each location they intend to hit to determine whether there is sufficient justification to warrant an attack. Further, the Commission is convinced that damage inflicted to some infrastructure was done for the sake of destruction.

4. Precautionary measures in attacks

(a) Warnings: leaflets, phone, text and loudspeaker messages

- From mid-July on, IDF began warning villagers in the south to evacuate their towns and villages. The warnings sere [sic] given by leaflets dropped by aircraft, through recorded messages to telephones and by loudspeaker. […]

[…]

- Military planning staff should pay strict attention to the requirement for any warning to be “effective”. The timing of the warning is of importance. In some cases IDF is reported to have dropped leaflets or given loudspeaker warnings only two hours before a threatened attack. Having given a warning, the actual physical possibility to react to it must be considered.

[…]

- Also of great concern was the physical danger [civilians] might face if they heeded the warning and took to the roads. There were number of civilians who, when warned by IDF to evacuate, did so only to be attacked on their way out. […]

- If a military force is really serious in its attempts to warn civilians to evacuate because of impending danger, it should take into account how they expect the civilian population to carry out the instruction and not just drop paper messages from an aircraft.

- To be truly “effective”, the message should also give the civilians clear time slots for the evacuation linked to guaranteed safe humanitarian exit corridors that they should use. Military staff should ensure that civilians obeying evacuation orders are not targeted on their evacuation routes.

- A warning to evacuate does not relieve the military of their ongoing obligation to “take all feasible precautions” to protect civilians who remain behind, and this includes their property. By remaining in place, the people and their property do not suddenly become military objectives which can be attacked. The law requires the cancelling of an attack when it becomes apparent that the target is civilian or that the civilian loss would be disproportionate to the expected military gain. Official statements issued during the conflict by Israeli authorities cast doubt on whether in fact they were fully aware of these obligations. For example, as reported on BBC news on 27 July, Israeli Justice Minister Haim Raimon said: “that in order to prevent casualties among Israeli soldiers battling Hezbollah militants in southern Lebanon, villages should be flattened by the Israeli air force before ground troops moved in”. He added that Israel had given the civilians of southern Lebanon ample time to quit the area and therefore anyone still remaining there could be considered a Hezbollah supporter. “All those now in south Lebanon are terrorists who are related in some way to Hezbollah”, Mr. Ramon said.

[…]

5. Attacks on medical facilities

- The Commission was able to verify that IDF had carried out attacks on a number of medical facilities in Lebanon, despite their protected character. An assessment by the WHO and the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health on the damage inflicted on primary health care centres and hospitals shows, for example, that 50 per cent of outpatient facilities were either completely destroyed or severely damaged, while one of the region’s three hospitals sustained severe damage. This study also reflects serious shortages of fuel, power supply and drinking water. […]

- In Tibnin, the governmental hospital showed signs of being hit by direct fire weapons, possibly a tank shell or a missile strike from a helicopter. The Commission saw at least five direct hits on the hospital’s infrastructure. According to reports received by the Commission, on 13 August, the immediate area of the hospital was the object of a cluster bomb attack – just before the ceasefire. According to these reports, the attack took place while some 2,000 civilians were sheltered in the hospital.

- IDF would know about the hospital, built on a hill and which stands out for miles around. Whether it had a Red Cross flag flying on its roof is relatively unimportant. In fact the small flag that the Commission saw flying on the hospital would be indiscernible from the air and possibly from the ground. This is in any case irrelevant because of the facts listed above.

- According to the information gathered, the Commission finds that from a military perspective there was no justification in either the direct fire on the hospital or the cluster bomb attack. The Commission did not find any evidence that the hospital was being used in any way for military purposes. Furthermore, Israeli intelligence drones, which were extensively used, would have clearly shown that civilians were sheltering in the hospital.

[…]

- According to international humanitarian law, medical units exclusively assigned to medical purposes must be respected in all circumstances. They lose their protection if they are being used, outside their humanitarian function, to commit acts harmful to the enemy. In this respect, the Commission finds that medical facilities were both the object of unjustified direct attacks and the victim of collateral damage. The Commission did not find any explanation by the Israeli authorities that could justify their military operations that affected, directly or indirectly, protected medical facilities. Israel’s general explanation that all infrastructure hit was used by the Hezbollah is insufficient to justify IDF’s violation of its obligation to abstain from carrying out attacks against protected medical facilities.

6. Medical personnel and access to medical and humanitarian relief

[…]

- The Commission took note that LRC [Lebanese Red Cross] reported nine different incidents involving ambulances and five others involving medical facilities that were targeted. In total, LRC had one volunteer killed, 14 staff members injured, three ambulances destroyed and four others damaged; one medical facility destroyed and four others damaged. […]

- On 23 July, at 2315 hours, two LRC vehicles were hit by munitions in Qana. The two vehicles were clearly marked with the Red Cross emblem on the rooftop. The incident happened while first-aid workers were transferring wounded patients from one ambulance to another. According to LRC reports and witness’ accounts, one ambulance left Tibnin with three wounded people and three first-aid workers on board. The second ambulance left Tyre with three first-aid workers on board. Both vehicles met in Qana in order to transfer the patients from one ambulance to the other. As the Tyre ambulance was about to leave, it was hit by Israeli missiles. A few minutes later, as the personnel of the Tyre ambulance tried to call for assistance, the Tibnin ambulance was also hit by a missile. The missile struck the ambulance in the middle of the Red Cross painted on the roof. LRC staff succeeded in calling ICRC, which managed to contact IDF to request that the attack be stopped. The Red Cross workers hid for around two hours, unable to provide assistance to the injured persons who were still in the vehicles. As a result, nine people, including six Red Cross volunteers, were wounded.

[…]

- […] The Commission did not find any evidence showing that these attacks were linked in any way to Hezbollah military activities. The Commission finds, therefore, that all these incidents constitute a deliberate and unjustified targeting of protected medical vehicles and personnel.

- The Lebanese Civil Defence was also the target of attacks by IDF. The Commission was informed that, during the armed conflict, one volunteer was killed and 59 other members of the Civil Defence were injured (11 staff and 48 volunteers). A total of 48 stations were damaged, as well as many vehicles.

[…]

- ICRC reported on several occasions the difficulties faced by LRC and ICRC to reach people in need of assistance. In a press briefing on 19 July 2006, Mr. Pierre Krähenbühl, ICRC Director of Operations, stated that the principal medical problem within Lebanon was finding ways to evacuate patients to hospitals. […]

- The Commission was also informed that ships loaded with humanitarian assistance that had left the port of Larnaca, Cyprus, were not able to enter Lebanese ports until late in the conflict both because of the blockade as well as because of delays in obtaining the required authorization from the Israeli authorities.

- Under international humanitarian law, “humanitarian relief personnel must be respected and protected”. Furthermore, “the parties to the conflict must allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need, which is impartial in character and conducted without any adverse distinction, subject to their right of control”. These rules apply whether the armed conflict is international or non-international. […]

[…]

7. Attacks on religious property and places of worship

- During its visit to south Lebanon, the Commission saw damage caused by IDF attacks on a number of places of worship. For instance, the Commission found that the village of Qauzah, a Christian village close to the Blue Line, had been occupied by IDF. Most of the villagers had left during the conflict but 10 persons remained. Of particular note was the damage caused to the Christian Maronite church, which was damaged by bombing in the early days of the conflict and was later occupied by Israeli forces and used as its base. The roof had been badly damaged and there was a large shell hole in the front right corner of the wall. The damage to the church’s roof and wall of the church appeared to have been caused by a tank round. Furthermore, during their 16-day occupation IDF vandalized the church, breaking religious statues, leaving behind garbage and other waste. The Commission saw a statue of the Virgin Mary that had been smashed and left in the church grounds. When the villagers returned, they found the church had been wrecked, the church benches and confessional box smashed. Silver items remained but had been deliberately broken. There were sandbagged defensive positions within the church grounds. There was no evidence to suggest fighting in and around the church to capture it. It therefore appears that IDF simply took it over. The damage was either caused on their occupation of the village or on their departure.

[…]

- In most of the incidents the damage to mosques or churches was only partial. Considering the nature of the destruction, the types of damage and vandalism caused and the use of some of these religious buildings and places of worship as temporary bases, it appears to the Commission that while there was clear intent for IDF to cause unnecessary damage to protected religious property and places of worship, their complete destruction was not aimed for.

- Under international humanitarian law, religious property and places of worship are protected during a conflict. Most of these rules are norms of customary international law, as confirmed by the ICJ in its advisory opinion on the legality of the threat or use of the nuclear weapons case [See ICJ, Nuclear Weapon Advisory Opinion]. It is also important to stress that the Rome Statute qualifies as a war crime intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion.

[…]

9. Internal displacement of civilians

- One of the most striking aspects of this conflict is the massive displacement of civilians which took place during the hostilities. According to Government estimates, 974,184 people – nearly one quarter of the population – were displaced between 12 July and 14 August, with approximately 735,000 seeking shelter within Lebanon and 230,000 abroad. Up to one half of the displaced were children. These figures must be considered against the demographic reality in Lebanon, where many people had already been displaced as a result of previous conflicts and communities still were in the process of recovery and rebuilding. The figures also include the secondary displacement of approximately 16,000 Palestinian refugees.

- […] As a result of the massive destruction of houses and other civilian infrastructure, displaced individuals and families were forced to live in crowded and often insecure conditions with limited access to safe drinking water, food, sanitation, electricity and health services. […]

[…]

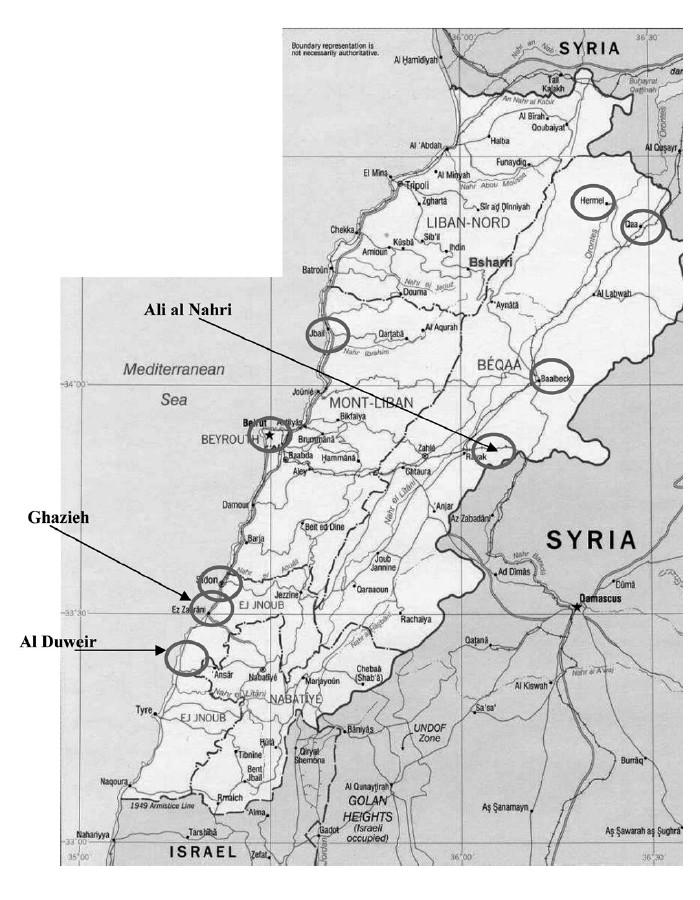

- Until the last days of the conflict, Ghazieh was seen as a safe haven for displaced civilians coming from the South and, according to the mayor, over 10,000 displaced people arrived in the town over the course of the conflict. According to witness testimonies, on Monday 7 August at around 0800 hours the town was attacked by Israeli air strikes. Several buildings were seriously damaged and at least three houses were completely destroyed by direct hits. Roads and bridges were also badly damaged, resulting in the isolation of Ghazieh from the main points of access into and out of town. […] In total, at least twenty-nine civilians died in Ghazieh between 6 and 8 August.

[…]

- International law prohibits forced displacement in situations of armed conflict, unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand. As set out in the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, before any decision is made requiring the displacement of persons, the authorities concerned must ensure that all feasible alternatives are explored in order to avoid displacement altogether. In particular, authorities and other actors must respect and ensure respect for their obligations under international law, including human rights and humanitarian law “so as to prevent and avoid conditions that might lead to displacement of persons”. Where no alternatives exist, all measures shall be taken to minimize displacement and its adverse effects.

- Much of the displacement in Lebanon was the result, either direct or indirect, of indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian property and infrastructure, as well as the climate of fear and panic among the civilian population caused by the warnings, threats and attacks by IDF. Furthermore, in many cases, the attacks were disproportionate in nature and could not be justified on the basis of military necessity. Taking into account all of these facts, the Commission notes that the displacement itself constitutes a violation of international law.

- The Commission further recalls that displaced persons are entitled to the full protection afforded under international human rights and humanitarian law. At the same time, they have specific needs distinct from those of the non-displaced population which must be addressed by specific protection and assistance measures. The Commission notes that, throughout the period of the conflict, IDPs often did not have access to humanitarian assistance to meet their needs.

Paras 209 to 246

10. Environment

- Already in the early stages of the conflict, IDF attacks on Lebanese infrastructure created large-scale environmental damage. The Commission considered the devastating effect the oil spill from the Jiyyeh power plant has had and will continue to have in the years to come over the flora and fauna on the Lebanese coast. This very serious event took place when the Israeli Air Force bombed the fuel storage tanks of the Jiyyeh electrical power station, situated 30 km south of Beirut. Due to its location by the sea, the attack resulted in an environmental disaster. The plant’s damaged storage tanks gave way. According to the Lebanese Ministry of Environment, between 10,000 and 15,000 tons of oil spilled into the eastern Mediterranean Sea. A 10 km-wide oil slick covered 170 km of the Lebanese coastline.

- The Commission was informed by the Director of the Jiyyeh power plant that the compound had been subject to two different attacks. The first strike took place on 13 July and was directed at one storage tank with a capacity of 10,000 tons of oil. Oil flowed from the tank but was held by the external retainer wall of the power plant building, which was some 4 metres high. Firefighters were able to put out the fire that ensued. The second attack, on 15 July, was directed at another storage tank, with a capacity of 15,000 tons of oil. The explosion and subsequent fire caused the explosion of another tank, with a capacity of 25,000 tons. The explosion and the very high temperature caused by the fire destroyed the retaining wall, thus leading to the massive flow of oil into the sea.

- The Commission is convinced that the attack was premeditated and was not a target of opportunity. Indeed, the strike was directly aimed at those tanks that had been filled in the days preceding the attacks. No missile was directed at empty tanks, nor at the main generator and machinery, which are just a few meters away from the storage tanks.

- The spill affected two thirds of Lebanon’s coastline. Beaches and rocks were covered in a black sludge up to Byblos, north of Beirut and extended into the southern parts of Syria. According to the Lebanon Marine and Coastal Oil Pollution International Assistance Action Plan prepared by the Expert Working Group for Lebanon, winds and surface sea currents caused the oil slick to move north, some 150 km from the source in a matter of a few days. This rapid movement of the slick caused significant damages on the Lebanese coastline, as well as the Syrian coast. Furthermore, due to the air blockade no air surveillance and assessment actions were possible. The only possibility left was to use satellite remote-sensing images. While cleaning up measures were undertaken a few days before the end of the conflict, under the authority of the Lebanese Ministry of Environment and the Lebanese Army, weeks after the ceasefire there were reports of oil slicks still floating in different areas.

- The Commission found that the environmental damage caused by the intensive Israeli bombing goes beyond the Jiyyeh oil spill. Damaged power transformers, collapsed buildings, attacks on fuel stations, and the destruction of chemical plants and other industries may have leaked or discharged hazardous substances and materials to the ground, such as asbestos and chlorinated compounds. These hazardous materials may gravely affect underground and surface water supplies, as well as the health and fertility of arable land.

[…]

- Furthermore, the Commission has also considered that direct attacks on fuel storage tanks and petrol stations, as well as on factories such as the Maliban glass factory, the Sai El-Deen plastics facility and the Liban Lait dairy plant, among others, have created increased risks of pollution by chemical agents that may have contaminated water sources, arable land and the air, posing a direct threat to the health of the Lebanese population.

- Article 35(3) of Additional Protocol I to the 1949 Geneva Conventions establishes a general prohibition on employing methods or means of warfare which are intended, or may be expected, to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment. Similarly, article 55(1) of the Protocol further indicates that special care shall be taken during armed conflict to protect the natural environment against widespread, long-term and severe damage.

- Furthermore, as indicated by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and reiterated in the legal literature, the principle that parties to a conflict shall take all necessary measures to avoid serious damage to the natural environment constitutes a norm of customary international law. […]

- Moreover, under article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Rome Statute, the intentional launching of an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment is considered a war crime.

- The Commission finds that, while Israel may argue that attacks on these facilities were justified under military necessity, the fact is that it clearly ignored or chose to ignore the potential threats these attacks posed to the well-being of the civilian population. While Israel may have attained its military objective, it did so by putting the health of part of the population at risk. The Commission does not see how this potential threat can be outweighed by considerations of military necessity. It thus finds that Israel violated its international legal obligations to adequately take into consideration environmental and health minimum standards when evaluating the legitimacy of the attacks against the above-mentioned facilities.

- Furthermore, the Commission holds the view that Israel should have taken into account the possibility that the attacks on the Jiyyeh power plant could lead to a massive oil spill into the sea. Despite the risks, IDF went ahead and attacked the site, with the consequences already explained. Whether the attack was justified or not by military necessity, the fact remains that the consequences went far beyond whatever military objective Israel may have had.

11. Attacks on cultural and historical property

- The Commission witnessed the damage on the Byblos archaeological site caused by the oil spill originating from IDF attack on the Jiyyeh thermo-electrical plant in Saida. The site, listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, suffered substantially from the oil pollution. In this respect, for example, the UNESCO Mission to assess the effects of the war on Lebanon’s Cultural Heritage indicated in its September 2006 report the following on this exceptional archaeological site[.]

[…]

- The Commission was able to verify the impact of the spill on the site’s coastal archaeological foundations. The Commission saw the damage to rocks and foundations caused by the oil, which according to the Ministry of Culture’s experts, has permeated the surface of the rock. […]

[…]

- After reviewing the material received and based on its visits to some of these sites, the Commission finds that Israeli attacks caused considerable and disproportionate damage to cultural, archaeological and historical property in Lebanon, which cannot be justified under military necessity. These unjustified attacks include, firstly, sites that, while not listed in the UNESCO World Heritage List, constitute nevertheless sites of extreme historical importance to the Lebanese population. That is the case of the destruction of sites in Chamaa, Khiyam, Tibnin, and Bent J’Beil. Second, Israel’s attacks in the vicinity of sites listed in the UNESCO World Heritage List, such as in the case of Baalbeck’s Jupiter’s temple, Byblos archaeological site and Tyre’s archaeological property, while not constituting a direct attack, caused important damage to specially protected property. The Commission finds that Israel could have and should have employed the necessary precautionary measures to avoid direct or indirect damage to especially protected cultural, historical and archaeological sites in Lebanese territory.

- Taking into account the number and gravity of incidents affecting protected cultural property, the Commission finds that these attacks constitute a violation of existing norms of international law and international humanitarian law requiring the special protection of cultural, historical and archaeological sites.

[…]

13. United Nations Peacekeepers – UNIFIL/Observer Group Lebanon

- During the conflict a number of UNIFIL and Observer Group Lebanon (OGL) positions were either directly hit by IDF fire or were the subject of firing close to their positions. All these United Nations positions are clearly marked, most are on prominent hill tops to aid observation. Their positions were notified in 12 figure grid references to IDF. On 12 July, IDF issued a warning to UNIFIL that “any person – including United Nations personnel – moving close to the Blue Line would be shot at”. On 15 July, UNIFIL was informed by IDF that Israel would establish a “special security zone” between 21 villages along the Blue Line and the Israeli technical fence. IDF informed UNIFIL that any vehicle entering the area would be shot at. This security zone was directly within the UNIFIL area of operation, which made it impossible to support (or evacuate, if necessary) many UNIFIL positions located in the zone. In effect, these warnings prevented UNIFIL from discharging its mandate conferred upon it by Security Council resolution 1655(2006) of 31 January 2006.

- The Commission found that there were 30 recorded direct attacks by IDF on UNIFIL and OGL positions during the conflict. These attacks resulted, among others, in the death of four unarmed United Nations observers at the Khiyam base. A staff member and his wife died in an air strike on their apartment in Tyre. In addition, five Ghanaian, three Chinese and one French soldier of UNIFIL were injured, together with one officer from OGL.

- It is significant that, towards the end of the conflict, after the ceasefire had been announced, there was a dramatic increase in IDF direct attacks on UNIFIL positions. For example on 13 August there were five direct hits, on positions at Tiri, Bayt Yahun, and Tibnin (on three occasions during the reporting period). There was extensive material damage in all these locations. On 14 August there were nine direct hits, on positions at Tibnin (four times), Haris (twice), Tiri (twice), and Marun al Ras (once).

- A total of 85 artillery rounds impacted inside these UNIFIL bases on these two days alone, 35 in Tibnin. These attacks caused “massive material damage” to all the positions. All UNIFIL personnel were forced into shelters, which prevented casualties.

- The attack on the UNIFIL Khiyam base of 25 July 2006 was a major incident during the conflict and is the subject of a separate UN report. […] UNIFIL records show that during the conflict a total of 36 IDF air strikes occurred within 500 metres of the base, 12 of these within 100 metres. In addition there had been 12 artillery bombardments within 100 metres of the base; four of these hit the base directly. While Hezbollah had a base 150 metres away, as well as some form of operational base in a nearby prison, UNIFIL reported that there was no Hezbollah firing taking place within the immediate vicinity of the base that day. Throughout 25 July, UNIFIL had protested directly to IDF after each of the incidents of close firing to the base.

- At 1925 hours on 25 July 2006 the base was struck by a 500 kilogramme precision-guided aerial bomb and destroyed. The United Nations Board of Inquiry noted that the Israeli authorities accepted full responsibility for the incident and apologized to the United Nations for what they say was an “operational level” mistake. The Board did not have access to operational or tactical level IDF commanders involved in the incident, and was, therefore, unable to determine why the attacks on the United Nations position were not halted, despite repeated demarches to the Israeli authorities from United Nations personnel, both in the field and at Headquarters. The report concluded that all standard operating procedures were followed and no additional actions could have been taken by United Nations personnel that would have changed the outcome.

[…]

- State practice treats United Nations peacekeeping forces as civilians because they are not members of a party to the conflict and are deemed to be entitled to the same protection against attack as that accorded to civilians, as long as they are not taking a direct part in hostilities. By the same token, objects involved in a peacekeeping operation are considered to be civilian objects, protected against attack. Under the Rome Statute, intentionally directing attacks against personnel and objects involved in a peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations constitutes a war crime as long as they are entitled to the protection given to civilians and civilian objects under international humanitarian law [See The International Criminal Court, Art. 8(2)(b)(iii)].

- The Commission has found no justification for the attacks on United Nations positions by IDF. Each United Nations position was clearly notified to IDF. In any case the locations have been in place for many years; they are easily recognized and built on prominent hilltop positions. There can be no doubt that both ground and air forces of IDF would have been fully aware of their locations. Firing of rockets by Hezbollah from the vicinity of these bases might explain the large number of “close firings” described above. However, from an international humanitarian law perspective of military necessity, and bearing in mind the principle of distinction, the Commission does not see how IDF can possibly justify the 30 direct attacks on United Nations positions and the deaths and injury to protected United Nations personnel.

- Furthermore, the significant increase in the bombardment of United Nations positions on 13 and 14 August cannot be described as being of imperative or even of vague necessity from a military perspective.

- With regard to Hezbollah firings from and into the immediate vicinity of United Nations positions, the Commission finds, based on the daily UNIFIL press releases, that there were six incidents of direct fire against UNIFIL positions and 62 incidents where Hezbollah fired their rockets from the close proximity of United Nations positions towards Israel.

- The Commission finds that Hezbollah fighters were using the vicinity of United Nations positions as shields for the launching of their rockets. This is an obvious violation of international humanitarian law and also put the United Nations forces in danger. However, “the vicinity” does not mean from within the bases as mentioned above. The direct targeting by IDF, when they have the advantage of modern precision weapons, remains inexcusable.

- The direct firing on United Nations positions by Hezbollah is equally illegal and inexcusable and would appear to be an attempt by them to blame IDF for such incidents.

Paras 249 to 275

14. Use of weapons

[…]

(a) Cluster munitions

- Cluster munitions were used extensively by IDF throughout Lebanon. These consisted of both ground-based […] and air-dropped […].

There is ample evidence pointing to a significant increase in the intensity of the overall bombardment including cluster munitions in the last 72 hours of the conflict, including the period after the adoption of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006). OCHA affirms that 90 per cent of all cluster bombs and their sub-munitions were fired by IDF into south Lebanon during these last 72 hours of the conflict. For example, cluster bombardments were particularly heavy in and around the Tibnin hospital grounds, especially on 13 August when 2,000 civilians were seeking shelter there.

- UNMACC, in cooperation with the Lebanese armed forces (National De-mining Office), has identified a total of 789 cluster strike locations throughout Lebanon. As of 31 October 2006, the estimate is that over one million cluster bombs had been fired in Lebanon. The reported dud rate of cluster munitions is as high as 40 per cent. In other words, many of the bomblets did not explode but, rather like anti-personnel mines, they littered the ground with the potential to explode at any time later.

- This wide use of cluster bombs has been admitted by Israeli forces. On 12 September, the Haaretz newspaper quoted an IDF unit commander stating that “[I]n order to compensate for the rockets’ imprecision, the order was to “flood” the area with them. … We have no option of striking an isolated target, and the commanders know this very well”. He also stated that the reserve soldiers were surprised by the use of MLRS rockets, because during their regular army service, they were told these are ‘judgment day weapons’ of IDF and intended for use in a full-scale war. An Israeli reservist soldier interviewed by the same newspaper also stated that “[I]n the last 72 hours we fired all the munitions we had, all at the same spot, we didn’t even alter the direction of the gun. Friends of mine in the battalion told me they also fired everything in the last three days – ordinary shells, clusters, whatever they had.” With regard to the exact timing of the launching of the cluster rockets, a unit commander said “[T]hey told us that this is a good time because people are coming out of the mosques and the rockets would deter them.” The commander also said that at least in one case, they were asked to fire cluster rockets toward “a village’s outskirts” in the early morning.

[…]

- Considering the indiscriminate manner in which cluster munitions were used, in the absence of any reasonable explanation from IDF, the Commission finds that their use was excessive and not justified by any reason of military necessity. When all is considered, the Commission finds that these weapons were used deliberately to turn large areas of fertile agricultural land into “no go” areas for the civilian population. Furthermore, in view of the foreseeable high dud rate, their use amounted to a de facto scattering of anti-personnel mines across wide tracts of Lebanese land.

[…]

(c) White phosphorous/incendiary weapons

- White phosphorous is designed for use by artillery, mortars or tanks to put down an instant smoke screen to cover movement in, for example, an attack or flanking manoeuvre. The phosphorous ignites on contact with air and gives off a thick smoke. If the chemical touches skin it will continue to burn until it reaches the bone unless deprived of oxygen. It is not designed as an incendiary weapon per se, for example in the same way as a flame thrower or the petroleum jelly substance used in napalm.

- The Commission received a number of reports concerning the use of this type of ammunition. On 16 July, Lebanese President Emile Lahoud and Lebanese military sources stated that IDF had “used white phosphorous incendiary bombs against civilian targets on villages in the Arqoub area” in southern Lebanon. In addition, the Commission was told about and witnessed a number of sites where the possible use of white phosphorous had occurred, among others, at Marwaheen on 16 July during the gathering of the civilians in the village prior to their evacuation under UNIFIL supervision. This was witnessed by civilians concerned and interviewed by the Commission. It was also confirmed by UNIFIL officers on the scene that 12 white phosphorous rounds were fired directly at the civilians.

[…]

(d) Dense inert metal explosives (DIME)

- Various media have reported on the possible use by IDF of Dense inert metal explosives (DIME), a new weapon, in Lebanon. It was reported that Israeli Air Force Major General Yitzhak Ben-Israel had described the weapon as being designed “to allow those targeted to be hit without causing damage to bystanders or other persons”. It was brought to the Commission’s attention by a number of expert medical witnesses that some of the casualties had suffered from inexplicable burn injuries not witnessed before. These witnesses had extensive experience of war wounds from previous conflicts; their testimony is therefore of some relevance. IDF have strongly denied the use of such weapons. If they were effectively used, the Commission finds that they would be illegal under international humanitarian law. Protocol I of the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects (hereafter “the Conventional Weapons Convention”) [See Protocol on Non-Detectable Fragments (Protocol I to the 1980 Convention)], to which Israel is a signatory, prohibits the use of any weapon the primary effect of which is to injure by fragments which cannot be detected by X-rays. The Commission was unable in the time available to thoroughly investigate the claims. However, in drawing attention to this weapon and in particular to the expert witnesses’ testimonies, it finds that the possible use of such weapons in Lebanon should be the subject of further investigation.

[…]

- None of the weapons known to have been used by IDF are illegal per se under international humanitarian law. However, the way in which the weapons were used in some cases transgresses the law. The use of cluster munitions has already been addressed. The Commission’s findings, detailed earlier in this report in relation to the direct targeting of civilian objects, infrastructure and protected property is at odds with the apparent interpretation of IDF and the application of the principle of distinction. The vast destruction of civilian objects throughout the Lebanon, but especially in the South where some villages were virtually completely destroyed indicates that weapons systems were not used in a professional manner, despite assurances from IDF that legal advice was being taken in the planning process. The record shows this: 1,191 persons killed; 30,000 houses destroyed; 30 UNIFIL and OGL positions directly targeted with 6 dead and 10 injured; and 789 cluster munitions strike locations.

15. Blockade

- On 13 July 2006 Israeli naval ships entered Lebanese waters to impose a comprehensive blockade of Lebanese ports and harbours. The next day, on 14 July, Israel’s air force imposed an air blockade and proceeded to hit runways and fuel tanks at Rafik Hariri International Airport, Lebanon’s only international airport.

- Israel justified the sea blockade with the argument that “[T]he ports and harbours of Lebanon are used to transfer terrorists and weapons by the terrorist organizations operating against the citizens of Israel from within Lebanon, mainly Hezbollah”. IDF further stated that “The Lebanese government is openly violating the decisions of the Security Council by doing nothing to remove the Hezbollah threat on the Lebanese border, and is therefore fully responsible for the current aggression.”

- In his 12 September 2006 report on the implementation of Security Council 1701 (2006) the Secretary-General informed the Council that he had undertaken discussions with all concerned parties and that Israel had lifted the aerial blockade on 6 September and the maritime blockade on 7 September.

[…]

- Parties to a conflict need to take into consideration the impact of the conflict on the civilian population. One of the most important aspects to consider is that of access to humanitarian assistance. Yet, as indicated by OCHA at the outset of the conflict, the Israeli-imposed blockade limited tremendously the work of humanitarian agencies by leaving only one entry point, by land, through Damascus. It was not until the second week of the conflict that Israel began considering expanding humanitarian entry points for relief aid to be sent into Lebanon. In this respect, for example, OCHA reported on 25 July that it was still seeking authorization for two ships arriving from Cyprus with an aid cargo to be allowed to land in Beirut. On 30 July, OCHA indicated that “the road between Aarida, on the Lebanon-Syria border, and Beirut is currently the only road open continuously”. Yet, on 4 August this road was also bombarded by IDF, thus seriously disrupting the overall provision of humanitarian aid. In general, access to ports in Beirut, Tripoli and Tyre was, at best, sporadic, thus forcing humanitarian agencies to continue using ground transportation through Damascus as the sole means for the transfer of aid supplies to the entire country. […]

- The Commission also considered the impact of the blockade on the environmental catastrophe that followed the Israeli attacks on the Jiyyeh power station. The Commission finds that the blockade unnecessarily obstructed the deployment of immediate measures to clean or contain the oil spill. It was not until shortly before the end of the conflict that initial clean up operations along the coast could actually be initiated under the authority of the Lebanese Ministry of Environment and the Lebanese Army. By then, the oil slick had moved north and had already contaminated a large extent of the Lebanese coast, including its archaeological sites, as well as parts of the Syrian coast. The Commission finds that the Israeli Government should have ordered an immediate relaxation of the blockade to allow the necessary urgent evaluation to be made, assessment measures to be adopted and the necessary cleanup measures to be carried out. In the view of the Commission there is no reason that justifies a failure to do so. Israel’s engagement in an armed conflict does not exempt it from its general obligation to protect the environment and to react to an environmental catastrophe such as that which took place on the Lebanese coasts.

[…]

- The Commission believes that the impact of the blockade on human life, on the environment and on the Lebanese economy seems to outweigh any military advantage Israel wished to obtain through this action. The Commission finds that the blockade should have been adapted to the situation on the ground, instead of being carried out in a comprehensive and inflexible manner that resulted in great suffering to the civilian population, damage to the environment, and substantial economic loss.

[…]

II. Human Rights Watch, Report on Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War

[Source: Human Rights Watch, Why They Died. Civilian Casualties during the 2006 War, Report, Vol. 19, No. 5(E), September 2007, available at www.hrw.org, footnotes omitted]

Why They Died

Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War

[…]

IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict

A. Applicable International Law

[…]

- There has been controversy over the humanitarian law applicable to Hezbollah. Unless Hezbollah forces are considered to be a part of the Lebanese armed forces, demonstrated allegiance to such forces, or were under the direction or effective control of the government of Lebanon, there is a basis for finding that hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah are covered by the humanitarian law rules for a non-international (that is, non-intergovernmental) armed conflict. Under such a characterization, applicable treaty law would be common article 3 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions […]. Whether captured Hezbollah or Israeli fighters would be entitled to the protections of the Third Geneva Convention for prisoners of war, the Fourth Geneva Convention for protected persons, or only the basic protections of common article 3, would depend on the legal characterization of the conflict and a factual analysis of Hezbollah and its relationship to the Lebanese armed forces. […]

[…]

VI. Hezbollah Conduct during the War

- Hezbollah was responsible for numerous serious violations of the laws of war during its conflict with Israel. […]

[…]

B. Hezbollah’s Weapons Storage

- Human Rights Watch documented a number of cases where Hezbollah violated the laws of war by storing weapons and ammunition in populated areas and making no effort to remove the civilians under their control from the area. Humanitarian law requires warring parties to take all feasible precautions to protect civilian populations in areas under their control from the affects [sic] of attacks. This includes avoiding deploying military targets such as weapons and ammunition in densely populated areas, and when this is not possible, removing civilians from the vicinity of military objectives. […]

- Intentionally using civilians to protect a military objective from attack would be shielding.

[…]

C. Hezbollah’s Rocket Firing Positions

- In most southern Lebanese villages visited by Human Rights Watch, local villagers consistently stated that Hezbollah fighters had not fired rockets from within the village, but from nearby fields and orchards, or from more remote uninhabited valleys. On a few occasions, Human Rights Watch was able to establish through eyewitness interviews that Hezbollah fighters did fire directly from inhabited villages, a practice that would have put the civilian population of those villages at great risk of Israeli counterfire. While international humanitarian law recognizes that fighting from or near populated areas is permissible if there are no feasible alternatives, Hezbollah did have alternatives when it fired from inside villages in the [majority] of cases examined by Human Rights Watch. This is evidenced by the fact that Hezbollah had bunkers and positions outside villages and was able to actually use them a great deal of the time.

[…]

D. Claims of Hezbollah “Human Shielding” Practices

- Israeli officials have repeatedly accused Hezbollah of using the Lebanese civilian population as “human shields” by deploying their forces – fighters, weapons, and equipment – in civilian areas for the purpose of deterring IDF attack. On many occasions, Israeli officials blamed these alleged shielding practices as the primary cause for Lebanese civilian deaths. […]

[…]

- A key element of the humanitarian law violation of shielding is intention: the purposeful use of civilians to render military objectives immune from attack.

- As noted above, we documented cases where Hezbollah stored weapons inside civilian homes or fired rockets from inside populated civilian areas. At minimum, that violated the legal duty to take all feasible precautions to spare civilians the hazards of armed conflict, and in some cases it suggests the intentional use of civilians to shield against attack. However, these cases were far less numerous than Israeli officials have suggested. The handful of cases of probable shielding that we did find does not begin to account for the civilian death toll in Lebanon. […]

- The Israeli government’s allegations seem to stem from an unwillingness to distinguish the prohibition against human shielding – the intentional use of civilians to shield a military objective from attack – from that against endangering the civilian population by failing to take all feasible precautions to minimize civilian harm, and even from instances where Hezbollah conducted operations in residential areas empty of civilians. Individuals responsible for shielding can be prosecuted for war crimes; failing to fully minimize harm to civilians is not considered a violation prosecutable as a war crime.

- To constitute shielding, there needs to be a specific intent to use civilians to deter an attack.

[…]

- […] Our investigation revealed that Hezbollah violated the prohibition against unnecessarily endangering civilians when they took over civilian homes in the populated village, fired rockets close to homes, and drove through the village in at least one instance with weapons in their cars. However, the available evidence does not demonstrate human shielding – the purposeful use of civilians to deter an attack – in `Ain Ebel. Hezbollah did not seize any inhabited houses in the village; even witnesses that criticized Hezbollah’s behavior agreed that Hezbollah took over only houses that had no one in them. While Hezbollah fired rockets from within the village, none of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch claimed that Hezbollah fired from or near homes that were populated at the time, or fled into populated areas of the village after firing their rockets. […]

[…]

E. Hezbollah Firing from Near UN Positions

- […] [T]here is strong evidence to suggest that Hezbollah fired much more frequently from the vicinity of UN outposts in southern Lebanon. According to reliable UNIFIL records, Hezbollah fighters fired rockets on an almost daily basis from close proximity to UN observer posts in southern Lebanon, often drawing retaliatory Israeli fire on the nearby UN positions as a result. There are two likely motives for this conduct, which are not mutually exclusive. On the one hand, the hills on which most observation posts are located are also good places from Hezbollah’s perspective for firing on Israel. On the other hand, Hezbollah commanders may have at times selected those positions for firing because the presence of UN personnel made it more difficult for Israel to counterattack. Insofar as the latter consideration motivated Hezbollah combatants, that would constitute shielding.

- Peacekeeping forces are not parties to a conflict, even if they are usually professional soldiers. As long as they do not take part in hostilities, they are entitled to the same protections under the laws of war afforded to civilians and other non-combatants. Deploying military forces or materiel near a UN base or outpost would violate at the very least the duty to take all feasible precautions to avoid harm to non combatants if there were feasible alternatives. Intentionally using the presence of peacekeepers to make one’s forces immune from attack amounts to human shielding.

[…]

F. Hezbollah Combatants in Civilian Clothes

- On the few occasions that Human Rights Watch researchers encountered Hezbollah fighters in the field during the conflict, those Hezbollah fighters were invariably dressed in civilian clothes, and often had no visible weaponry on them. Especially away from the frontlines, Hezbollah fighters appear to have operated in small cells of fighters, dressed in civilian clothes and maintaining contact with each other as well as Hezbollah fighters in other cells with handheld radios. Away from active areas of combat, Hezbollah fighters were normally unarmed, keeping their weapons out of sight until needed. Only during active confrontations with Israeli forces did some Hezbollah fighters, particularly Hezbollah’s elite fighters, fight in military uniforms.